Daniel Z. Lieberman is a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences at George Washington University. Lieberman is a recipient of the Caron Foundation Research Award, and has published over 50 peer-reviewed articles and book chapters. He is the co-author of the international bestseller The Molecule of More and the author of Spellbound: Modern Science, Ancient Magic, and the Unconscious Mind.

Zan Boag: Clearly, given your research and writing, we’re going to be speaking about dopamine, but I’d like to look at it through the lens of novelty and the influence of novelty in our lives – why we’re drawn to it and what sort of effect this has on the decisions we make throughout our lives. But first I wanted to find out a little bit about dopamine in humans. Are we the only animals who have dopamine? And why does it exist in our brains at all?

Daniel Lieberman: We are not the only animals who have dopamine, but we certainly have more sophisticated dopamine circuits than any other animals; all mammals have it. It might be surprising to hear that the animal that has probably the most dopamine after humans are corvids – crows, blackbirds. And if you go on YouTube, you can see them solving these multi-step problems. There’s food that they can’t get without a tool like a stick, but the stick can’t be obtained without solving some other problem. And they go through this in a brilliant way. They’re very, very clever. But other animals that we think of naturally as intelligent, such as dolphins and apes, they also have significant amounts of dopamine as well.

I’d like to stop you for a second there. How does dopamine relate to intelligence?

I think we need to take a little bit of a step back to answer that question, and we do have to talk a little bit about what dopamine is and what it does. Most people think of dopamine as being the ‘reward molecule’. It gives you a kick when you experience novelty or some other kind of reward, like eating when you’re hungry, finding a new romantic partner, that sort of thing. And that’s an important part of what dopamine does. But more generally, what it does is it orients us to maximising resources in the future. So for example, if there is an attractive reproductive partner out there, we’ll get dopamine, and that will give us the desire to be with this person. It will give us the motivation to do all the hard work of getting dressed up and going out to a club, and then it will give us the excitement.

That’s part of what dopamine does. It gives us desire and motivation for things that have the potential to make our life better, and that is active in a circuit deep inside our brain. But there’s another dopamine circuit that gives us the tools to accomplish these things. And that’s a dopamine circuit in the frontal lobes, which is the most advanced part of the brain in humans. Dopamine is very much about the future. Unlike the present, the future does not have a physical existence. It’s all hypothetical, it’s all possibilities. When I think about what I’m going to do after this interview, it is just imaginary. It’s not real.

Since dopamine evolved to help us think about things that were not yet real, humans were able to adapt that to allow us to think about abstract things, things like logic, reason, justice, beauty, music, all of these other things that don’t have a physical existence – the laws of science, chemistry, and that all involves these frontal lobes that are more advanced in humans than any other animals. And so dopamine has moved from this thing that gives us desire and motivation to something that really allows us to master our environment by using these abstract laws of nature, of science, and even of aesthetics to mould the world, to allow us to extract the maximum amount of resources.

I can’t help but think of another question that I wanted to ask you that was related to the effect that dopamine has on love and our desire to seek partners. You use the example of Mick Jagger and George Costanza – that when it comes to love, they’re essentially the same person. Now, what issues do people face, clearly not just Mick Jagger and the fictional George Costanza, but what issues do people face when it comes to dopamine, novelty, and love? I’m thinking in particular how people have an ease of access to potential partners through dating apps or social media and so forth. Does this have an effect on how people seek love and their ability to retain a partner?

So our brains evolved in an environment of scarcity. We were always living on the brink of starvation. And so having this dopamine drive to constantly go out and seek things that are going to make our future more secure was very adaptive and very helpful for us. But we no longer live in an environment of scarcity. We now live in an environment of plenty and the dopamine system that was so useful to our evolutionary ancestors has become a potentially dangerous liability. We see that most clearly with food. The problem today in most countries is not starvation, it’s obesity because these dopamine circuits that would make us work as hard as we could to find sources of food to prevent starvation now make us gorge ourselves on potato chips and French fries and that sort of thing. And it’s very similar with love. The days when we would have to work very, very hard to find one partner are not so very old.

Maybe a hundred years ago, maybe 50 years ago, it was like that. Now we’ve got these dating apps that are basically like 7-Eleven for junk food, but for sex and partnership. And so, when we experience love, we go through different stages. There’s a dopamine phase and there’s a non-dopamine phase as well. The dopamine phase is the excitement of the new partner, and we get very excited thinking about being with this person. And if we actually fall in love with them, our dopamine goes off the charts. Some people say that falling in love is the single most pleasurable experience human beings have in their lifetime. But love, passionate love, being in love, only lasts about nine to 12 months. And at that point it fades, and that’s how it is with all dopamine-related things. You get very, very excited about buying a new TV, a new car, a new pair of sneakers, and that excitement fades very, very fast.

Mick Jagger and George Costanza didn’t last nine to 12 months with each partner though, did they?

They did not. Because the more you do this, the less it lasts. It’s sort of like a drug addict. They develop tolerance, their brain changes. And so what I think that we’re not good at in modern society, because this is not something that is taught or encouraged, is how to make that transition from a dopamine love that is intense, but short-lived, to a longer-lasting love that’s called companionate love and is mediated by different brain chemicals.

With the prevalence of social media and dating apps, it becomes very difficult for those who are growing up in an environment where nobody’s really learned how to deal with this – they’re now faced with an almost unlimited choice of partners. And also if things get tough after that nine to twelve months of dopaminergic love, and they don’t have that same rush that they had in the beginning, well, it’s very easy for them to just move on. They can swipe again and move on. I just wonder how people are going to learn to deal with this process, something older generations didn’t have to deal with when they were growing up.

We’ve spoken a lot about the joy of novelty, but there’s also a joy of familiarity. Sometimes we like to experiment, go to a new restaurant we’ve never been to before. Other times we want to go to our favourite place. And with normal human variation, there’s variation across the spectrum: some people have more dopamine, and they want exciting things. Some people have more of these other neurotransmitters, they want things the same. The problem is that our society is always trying to push us in the direction of the dopamine side, because that’s what makes money in a capitalist economy.

If you kind of say, “I love the stuff I have, I don’t want to buy anything else,” that’s not going to work. And so messages we get through media, which we consume more and more, are always trying to push us towards the dopamine side. Even people that might be congenitally predisposed to meet one person and be happy for the rest of their life, society’s saying, no, no, no, no, no, don’t do that. Swipe, swipe, swipe, swipe, swipe, new, new, new, new, new. So in terms of future generations, the first step is people reading books like The Molecule of More and getting an insight into what’s going on inside of their brain. How are they being manipulated? And are these dopamine thrills really in the best interest of their long-term happiness? So we see in culture these swinging pendulums, they go back and forth.

I happen to be an optimist by nature, and so I think it’s very possible that future generations will kind of open up their eyes and say, “This is not working out. We need to revisit some of the older traditions that existed for centuries for a reason, because by and large, they worked pretty well. And this new novelty of sleeping with somebody new every week, it looked bright and shiny at first, but ultimately it turned out to be unsatisfying.” So I’m hoping the pendulum will swing back and people will try to balance the joys of novelty with the joys of familiarity.

It’s interesting you talk about capitalism, I have a quote here from you about consumption – you say, “We don’t need a new cell phone. We don’t need a bigger TV. We should just experience what we have and enjoy it.” Now, many of us know this deep down, but we are still lured by ‘the new’, by novelty, partly because we’re consuming so much media. But ‘the shiny new’ seems to grab people. How do we shift from being future focused, from being novelty-seeking, with the unlimited potential outcomes on offer? How can we live more in the here and now?

The first thing we have to recognise, we have to have a little humility and recognise that we are animals; and that although it feels like we can control our thoughts, we have a lot less control over them than we think we do. We think that we can make choices, but we have a lot less control of our choices than we think we do.

Fill your kitchen with junk food and then see if you can eat healthy. You can’t. If you want to eat healthy, you have to throw away all the junk food and fill your refrigerator with healthy things, because our ability to make choices is limited. There’s a wonderful quote, and I can’t remember who said this: “We don’t determine our fate. We determine our habits, and our habits determine our fate.” So what that means is that we’ve got to take a long-term view. And if we want to make good decisions about big things, we’ve got to make good decisions about little things. And we’ve got to be patient and understand that it takes a lot of time. We have to understand there’s going to be two steps forward, one step back, not beat ourselves up, but we’ve got to think about what kind of habits are going to promote being able to step away from being controlled by dopamine and by people who are trying to sell us things we don’t need to just living in the present moment and having joy.

So maybe the first thing we might do is delete certain apps from our phone. We might limit the amount of time on social media. We get on social media, maybe set a timer and say, “OK, that’s it.” Establish some habits like daily meditation that brings us into the here and now. It gets our mind off of what might be in the future and trains our mind, just like an athlete would train their body, to be in the present moment. So instead of watching Netflix, taking a walk outside in nature, maybe with someone we care about, a partner or a good friend. In order to make the big change in our brain, we’ve got to make a thousand little changes.

You talk about being controlled by dopamine and the fact that we do have to make these small changes, and in an earlier interview you also spoke about how dopamine can actually determine our ethical approach. In that interview, you referenced the infamous trolley problem when discussing this matter. How large a part does dopamine play in determining what we deem to be the right thing to do in a particular situation?

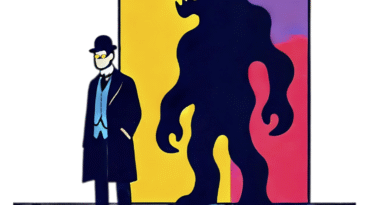

First of all, we have to acknowledge that we don’t always do the thing that we deem to be the right thing. So, for example, I may have the opportunity to make some money, but it’s not entirely ethical. I may choose to do it anyway, because of the desire aspects of dopamine saying, “Wow, it’d be really nice to have that money.” And that would be the deep dopamine circuit. But if we turn to the more advanced dopamine circuit in the frontal lobes, it’s going to help us make ethical decisions based on logic. And typically what that leads to is a utilitarian approach to ethics that is maximising the good for the most people. And that sounds like a wonderful ethical approach, and it is, in many ways.

But it also means that you can sacrifice some people for the greater good. And we see that in the trolley problem, sacrifice the one life in order to save the five lives. And that makes sense in some situations, but in other situations, it breaks down. As part of my career, I did research and sometimes we would have these wonderful medications that would have the potential to vastly benefit humanity, but nobody wanted to sign up for the clinical trials because of the risks. So a utilitarian approach would be to lie about the risks, because yes, these people might get hurt, but that’s OK because thousands, maybe millions of people are going to be helped.

Now, obviously, that’s not an ethical approach that anybody is going to accept. The alternative ethical approach is deontology or harm avoidance, and that says, you may not intentionally harm someone, even if other people will benefit. And that’s what we follow in clinical research, we require informed consent. We can’t deceive these people. So I think that dopamine pushes us towards this utilitarian approach to maximise the good for the most people. But it can be very, very scary because it can lead to very scary things in which individual rights become subservient to the greater good, and that can lead to things like totalitarianism.

It’s a slippery slope. It can be dangerous territory there.

Yes, very dangerous.

Given that dopamine is all about the future, this will have an effect on our desire for new things, but it can also have an effect on how we feel about consumption after we’ve purchased something. Everyone has experienced this, where they’ve felt like they really needed something, they go and buy it, and within a day or two, they may feel buyer’s remorse. Can you explain a little bit about what effect dopamine has on buyer’s remorse?

When dopamine circuits are active, it gives us feelings of excitement and anticipation, of desire, all of these pleasurable things. There’s a great quote in A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, Christopher Robin asks him, “What do you like best in the world?” And Pooh’s about to say eating honey, but then he remembers there’s a moment just before he starts to eat honey that’s even better, and that’s the dopamine. Now here’s the problem: our dopamine circuits only process information about the future. So if a potential ‘good’ exists in the future, our dopamine circuits will be active. But as soon as the future becomes the present, it goes outside of the realm of dopamine processing and into the realm of other chemical processing in the brain. And so what happens when the future becomes the present, dopamine shuts down, and that feels kind of awful, having dopamine shut down.

Imagine standing in line. I really like lattes and so a lot of times I’ll go to the store and get a latte. You stand in line; you’re thinking about your latte. You get to the front of line, and they tell you the latte machine is broken. Boom, dopamine comes down and you feel resentful and deprived and pissed off. That’s the same thing that happens when you buy something that you really want, because what is possible becomes what is. Now, there can be great joy in what is, but it’s not dopamine, and as we talked about, we tend not to be very good with those other chemicals, and so you get dopamine down, the other one up, but we’re not good with that other one, so we don’t experience it. All we experience is boom, dopamine drops. Why did I spend all of this money on this jacket? It’s not transforming my life the way dopamine told me it would.

You talk about ‘the fall’ afterwards and the rush prior to consuming or experiencing something new. It reminds me a lot of addiction. What role does dopamine play in addiction to new things or new experiences? Are people addicted to the dopamine, the effect of the dopamine rush for experiences or things, or in the case of drugs, is it the drug itself?

All drugs of abuse, drugs of abuse affect us in different ways. Cocaine is different from alcohol, but they all have a final common pathway of boosting dopamine in the reward centre of the brain. Now, getting addicted to drugs is a little bit different than getting addicted to things like shopping or sex or the internet. And that’s because the drugs have a direct chemical effect on the reward centre, and so they are not liable to the modification that other circuits bring in with more natural behaviours. And so drugs bypass all of that. They blast dopamine and it makes us feel like we’ve just hit a home run in the World Series, or we have just won the Nobel Prize. You get natural dopamine before, looking forward to doing that hit. You get artificial dopamine during, and then after you get a crash like nobody’s business.

Because you’ve had the double dose.

You’ve had the double dose, and the artificial stimulation takes it up so much higher than anything natural that it breaks the system. When you get that dopamine crash afterwards, you’re absolutely miserable and you are obsessed with getting more of the drug to get yourself back up there. To say you’re addicted to the drug, say you’re addicted to dopamine, it’s kind of the same thing because it’s the drug that’s blasting the dopamine.

Now with non-drug addictions, like we can say for example, social media addictions, it’s not exactly the same, because you are going through the natural pathways without distorting them chemically, but you are destroying them in a different way. It’s sort of like the food companies did an enormous amount of research so they could make ultra-processed foods that would maximally stimulate dopamine. We do get addicted to those things. By the same token, social media companies like Meta, they have neuroscience experts on their staff studying ways to maximally stimulate dopamine with their algorithms, with their interfaces, in order to make it as addictive as possible.

I’m getting the sense that in contemporary society, dopamine is abundant. It’s not something we really need to seek out anymore. It seems to be something that we need to try and decrease rather than increase; the ability to have that dopamine hit is everywhere. Do we need to be looking at ways to decrease the amount of dopamine that we have in our lives? To get enjoyment out of things that we already know, that we’ve already experienced, the commonplace or the known? Do we need to make that shift from high-level dopamine to a lower-level dopamine life?

I think absolutely that’s right. With modern technology, it’s become easier and easier to make dopamine abundant. But as we talked about earlier, you develop tolerance to dopamine. The first hit of cocaine is going to get you higher than anything else, and it’s the same with things like social media and ultra-processed food and meaningless sex. It stops giving us pleasure after a while. You know about doomscrolling. You’re looking for that dopamine hit. It’s not coming, but you can’t stop because you’re enslaved by it.

So I think that we need to be a little bit more deliberate in the choices that we make, and we need to ask ourselves why. Am I clicking on this link because I really think it’s going to make me happy, or am I clicking on this link because somehow I’m chained to the computer and I can’t get up and go outside and go for a walk?

Dopamine is powerful. It’s very hard to overcome addictions, but it’s not impossible. And if we ask ourselves, well, is there anything more powerful than dopamine that we can pit against it to try and free ourselves from this enslavement? The answer is social interactions, when you’re just enjoying being with somebody, you’re not trying to seduce them. You’re not trying to sell them anything. You’re not even planning a vacation with them in the future. You’re just enjoying being with them, there’s no dopamine there. Those are all here and now in the present chemicals, and that’s also a pretty wonderful thing.

And it’s no coincidence that when people are battling addictions, they don’t try to do it on their own, because that’s not going to work. They create a support system.

Social media, which has gotten so addictive with dopamine, with the likes and how many friends do you have? That originally started out based on the non-dopaminergic joy of connecting with people. It originally wasn’t about meeting strangers. It was about a new way to share things with people that you were connected to in real life. That’s why it took off. I think that that’s where the salvation is going to come from.

Society as a whole saying: “This is no longer cool; you no longer fit in by having the most followers and the most likes; you no longer fit in by wearing the latest fast fashion; you fit in by being able to establish meaningful relationships with other people.” I think we’re seeing glimmers of that, and I think that as we get more and more insight into the fact that constant dopamine is a dead end that’s not going to take us anywhere, it’s not going to make us grow, it’s not going to give us satisfaction, I hope we’re going to gradually shift more into the direction of appreciating other people in our social contacts.

I really like that. It seems like you’re advocating a shift from consumption to connection.

I think that’s a wonderful way of saying it. Beautiful, the alliteration.

From the Novelty edition of New Philosopher, available from our online store.