“Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works. Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it. Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.”

- Douglas Adams

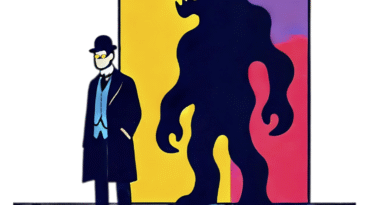

The human love of novelty could be said to be little more than a desire to suppress boredom. So fearful are our minds of becoming bored that we will latch on to anything to keep ennui at bay.

The phenomenology of boredom has been studied by philosophers since medieval times. In his essay, On Tranquility, the Roman philosopher Seneca refers to boredom as “an agitation of a mind which can find no issue because… of the hesitancy of a life which fails to find its way clear.” In other words, we suffer boredom when we are restless for something, but do not know exactly what that is. We yearn to be mentally occupied – to have a goal, a plan, a desire – but nothing seems to pique our interest in any meaningful way. We wish to be consumed by a task that makes time flow, rather than drag.

Central to boredom is a sense that life is on repeat – a ceaseless repetition of daily routines with each day much resembling the next. “How long the same things?” writes Seneca. “Surely I will yawn, I will sleep, I will eat, I will be thirsty, I will be cold, I will be hot. Is there no end? But do all things go in a circle?”

It is the nature of the human mind to be active, naturally restless and desirous of action, so when nothing novel is forthcoming, a quiet agitation can creep in. It’s why the bored today reach for their phone or their computer, or mindlessly eat as an antidote to this insufferable affliction.

But we needn’t be afraid of boredom, argues British philosopher Bertrand Russell. “All great books contain boring portions, and all great lives have contained uninteresting stretches… No great achievement is possible without persistent work, so absorbing and so difficult that little energy is left over for the more strenuous kinds of amusement.” Rather, the onset of boredom should signal that we are momentarily mentally disengaged – and needful of change, a break, or new ways of connecting to the world.

From the news section of the Novelty edition, which can be purchased here