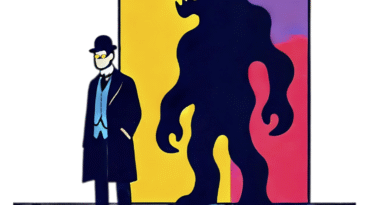

“I do think that people literally get addicted to cell phones and social media, yes. It’s important to recognise that addiction is a spectrum disorder, and it is possible to be a little bit addicted. Also, the same brain mechanisms that mediate severe addiction also mediate our minor addictions. So we’re all evolutionarily designed to approach pleasure and avoid pain. And that kind of neurobiological wiring is exactly what has kept us alive for millennia. And it’s also the very same wiring that makes us all vulnerable to addiction. So I don’t think that anybody is immune from this problem. And I do believe that smartphones are addictive. They’ve been engineered to be addictive and that doesn’t really – you know, we don’t really need more studies to show that that’s true. All you need to do is go outside and look around.”

– Anna Lembke, Chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic at Stanford University

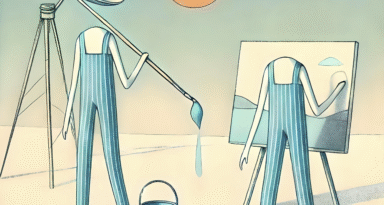

When scientist Maria Sklodowska first laid eyes upon Pierre Curie standing in the recess of a French window, she was struck by his open expression and the slight detachment in his attitude. “His smile, at once grave and youthful, inspired confidence,” she recalled. Maria had been hunting for laboratory space and a mutual colleague suggested she meet Pierre, an established physicist and laboratory chief. A year later they married.

Today, 381 million people worldwide do not rely on serendipity or chance encounters to find love, but dating apps, a consumer product birthed from recent developments in smartphone, mobile internet, and cloud computing technology. Users on dating apps pay a monthly fee to a company to search for love, thereby making dating apps the quintessential capitalist creation – turning love into profit.

In his book, In Praise of Love, French philosopher Alain Badiou likens dating apps to an arranged marriage where “advanced agreements” replace “chance encounters and in the end any existential poetry”. Within the search interface, users are presented with profile shots of prospective ‘lovers’ in much the same manner as any e-commerce offering – from vacuum cleaners to air fryers. Users swipe right on profiles or press ‘like’ or a ‘heart icon’ – and if the buyer and seller come to a ‘match’, a market transaction is consummated, prompting an introductory message.

Central to Badiou’s philosophy is the idea that love is an event, an unpredictable encounter, that challenges the existing order and creates something novel. He argues that true love requires embracing the risk of the unknown and the possibility of transformation. “Love isn’t simply about two people meeting and their inward-looking relationship: it is a construction, a life that is being made, no longer from the perspective of One but from the perspective of Two,” he writes.

But dating apps, which advertise their services with slogans such as “Get love without chance!” and “Be in love without falling in love!”, seek to minimise the risks and vagaries of love. Certainly, one can mitigate the risk of ‘falling’ in love and being hopelessly heartbroken when there are quite literally tens of millions of other possible candidates to take their place.

But love cannot be reduced to the first encounter, stresses the philosopher. Love takes time to flourish. It is a “tenacious adventure”. One needs a good dose of tenacity to not give up at the first hurdle, disagreement, or quarrel. “Real love is one that triumphs lastingly, sometimes painfully, over the hurdles erected by time, space and the world.” Of course, the duration of time necessary for love to flourish, as Badiou describes, is hampered somewhat in the gamified world of dating apps. And in true capitalist fashion, no dating app wants to see its user-base diminished by the attainment of love, but rather it demands that players keep on searching, ad infinitum.