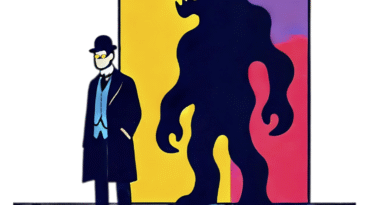

“[The] selective concern with the ‘inner drama’ enables the writer or artist to capture the essential feature of human experience; it allows him to penetrate beneath the encrusted surface of ordinary experience to the hidden and unfamiliar significance beneath it. In this way the artist can often make us see the familiar in a new light. As Anaïs Nin writes: ‘It is the function of art to renew our perception. What we are familiar with we cease to see. The writer shakes up the familiar scene, and as if by magic, we see a new meaning in it.’”

– Orville Clark

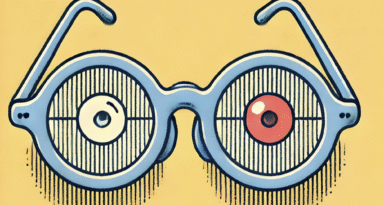

The news media has been described as a “time machine” because it is deliberately short sighted. The news media could also be called a “novelty machine” due to its emphasis on the new – a novel episode, disruption, or interruption – that stands out due to its break from the familiar or routine. A random act of violence or a shock fall in the stockmarket will demand more media space than a chronic issue that plagues society over the long term. “For this reason, society’s biggest problems do not routinely dominate media coverage,” writes Thomas E. Patterson, Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Novel stories stimulate interest and curiosity, and news organisations, which operate under the economic imperative of attracting and retaining a large audience for advertisers, rely on citizens’ “need to know” (otherwise known as click-bait) for survival. “The latest news abruptly replaces the old… Each day is a fresh start, a new reality. Novelty is prized, as is certainty. Journalists must have a story to tell, and it must be a different one than yesterday’s,” Patterson writes in Time and News: The Media’s Limitations as an Instrument of Democracy.

Patterson argues that as political parties and representative institutions have weakened, the public increasingly expects the news media to take a lead role in setting the public agenda, and organising public opinion and debate. But the news media are poorly suited to this role, he argues. News stories require a specific event to give the story a sense of immediacy, and policy matters are by their very nature drawn out affairs extending over months or many years. Few news stories manage to get repeat airtime, wiped out by more ‘pressing’ events – producing in the news media a chaotic disjointedness, much like a case of ADHD, where the immediate or urgent is preferenced over sustained thinking. The news has become “an endless stream of emergencies,” argues critic James Fallows. Whereas chronic societal problems tend not to change much from day to day, and therefore receive scant media attention.

Perhaps more concerning is the illusion of ‘reality’ one gets from perusing the news. People feel as though news media gives them an insight into the broader economic and societal picture, but Patterson argues that this sense is largely misguided. He cites a Swedish study by Jörgen Westerståhl and Folke Johansson, which examined the media’s coverage of seven major policy areas, such as crime, the economy, and defence, and found that “in practically no case was there any correspondence between the factual and the reported development”. It explains why economic shocks (property and stockmarket crashes) come almost ‘out of the blue’ for investors when, in actual fact, crashes are a result of a cumulative building up of pressure over a period of time. The bigger picture is lost in a sea of ‘right now’ emergencies – the media being less a mirror of a society than a daily collage of the day’s most novel events.