“Nothing is more free than the imagination of man; and though it cannot exceed that original stock of ideas furnished by the internal and external senses, it has unlimited power of mixing, compounding, separating, and dividing these ideas, in all the varieties of fiction and vision.”

- David Hume

Close your eyes and imagine a new colour. Not a new shade of an existing colour, but a completely new colour, one you’ve never seen before. Got it? OK, good. Now, imagine that we’re...

Sorry, what? You say you’re having trouble visualising a new colour? You keep trying, but no matter what you do, every ‘new’ colour you imagine is just some variant on all the other colours you have seen before?

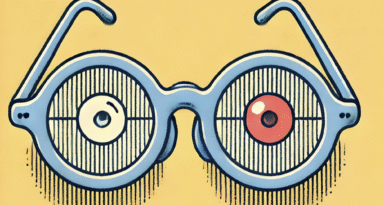

Well, don’t feel too bad. After all, you’re only human, so you can only see light within a certain spectrum. If you were a sparrow, a dog, or a bee, you’d be able to see ultraviolet light as well. (Many flowers would look very different to you, and much more visually complex). Some humans can see UV light too, in fact, due to lacking a lens; they say UV looks whitish-blue. But for the rest of us, the physics of light and the biology of our eyes and brains mean we’re limited to a certain, albeit still very rich, range of possible colours.

The idea of a wholly new colour is one that science fiction writers have been playing around with for decades. H.P. Lovecraft’s chilling 1927 story The Colour Out of Space imagines a meteorite hitting a Massachusetts farm, bringing with it an alien entity which poisons the landscape and deforms and deranges both humans and animals. This life form is nothing like any organism we’ve ever seen. It takes the form of a completely new colour, “almost impossible to describe; and it was only by analogy that they called it colour at all.”

Now, there’s another question: even if you could see a completely new colour, either in your imagination or in the world, how could you then explain what it looked like? When people who have been unable to see since birth are asked things like, “do you just see black?” many struggle to answer, precisely because they don’t know what ‘black’ looks like. The problem here is that our colour definitions are what philosophers of language call “ostensive”, the sort of thing you learn by someone pointing at something. We know what blue is because we’ve seen enough blue things to use the concept successfully, and we can learn new colour-names by alluding to objects of the same hue (“duck-egg blue”) and even argue about them (“no, I’d say that’s more cerulean than cobalt”).

But how would you do that with a completely new colour? Lovecraft, for instance, doesn’t even try. Under some experimental conditions it seems people can see otherwise impossible combinations of ‘opposing’ colours, such as red and green. A 1983 study claimed that some participants, when presented with just the right visual stimuli, were indeed able to see new combined colours such as redgreen or blueyellow. Some even reported being able to visualise the new colour after the experiment was over, at least for a while. But they struggled to describe what they’d seen, beyond descriptors like ‘reddish-green’. Try imagining ‘reddish-green’ and see how far you get. It seems that without actually seeing a new colour, we can’t even imagine it. Why?

Philosophers have long recognised our imaginations aren’t limitless. Most philosophers accept that we cannot imagine things that are conceptually (not just physically or practically) impossible, for instance. In the 18th century, David Hume argued that we cannot conceive a mountain without a valley, for instance – and, as we cannot conceive such a thing, we decide that it’s not actually possible.

(Presumably, for Hume, the bottom of a mountain standing on a plain would still count as a valley. No disrespect to the father of the Scottish Enlightenment, but honestly it’s not his best example.) You can think phrases like “mountain without a valley” or “square circle” or “triangle whose interior angles sum to more than 180 degrees” all you want. But when you do so, whatever you’re imagining won’t really be that. There’s simply nothing for a square circle to look like. (What about those M.C. Escher-style drawings of ‘impossible’ staircases and the like? They’re optical illusions. They couldn’t exist in 3D.)

For Hume, no matter how powerful our imagination is, “it cannot exceed that original stock of ideas, furnished by the internal and external senses”. Ideas, on Hume’s empiricist model, are the echoes of impressions – that is, things we’ve previously encountered with our senses. Complex ideas are made up of simple ideas, and simple ideas, in turn, are copies of simple impressions. Perceptions, not concepts, are the fundamental building blocks of our entire mental lives.

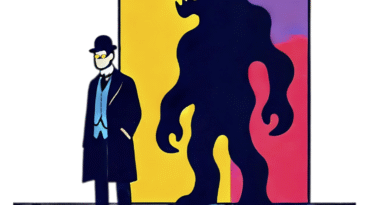

If Hume is right, there’s nothing really new in our heads, because everything in there came in through our eyes and ears first. Look close enough, and anything you imagine will turn out to be made up of more basic elements you’ve previously experienced. That still leaves imagination with a very wide scope, because the possible combinations of our simple impressions is vast. Ultimately, though, even the most original, plucked-from-thin-air thing you can imagine is a mosaic made up of things you’ve previously seen (or heard, smelled, touched, or tasted) at some point in the past.

Needless to say, not everyone agrees with Hume. But there does seem to be something to the idea that when we try to imagine completely new things, we can only work with what we already have. If I ask you to imagine a totally new animal, the odds are pretty high that what you’ll come up with is based on some animal you’ve seen, or at least seen a picture of. Perhaps, like the centaur or the unicorn, it will be a sort of Frankenstein’s monster, composed of parts of other, more familiar animals stuck together. The first person to come up with the idea of a unicorn had clearly seen both a horse and a narwhal horn before, and the inventor of the mermaid was familiar with both humans and fish. Even the most outrageously weird aliens in science fiction always seem to have some sort of similarities with organisms we’re more familiar with, such as limbs, eyes, and mouths. That’s not just to make the costumes cheaper, either: if they were too different from all the other life forms we’ve come across, audiences would likely struggle to recognise them as aliens at all.

In fact, that was precisely Lovecraft’s motivation for making his extraterrestrial menace a new colour. Instead of little green men he wanted to come up with something truly alien, something that confounded our very sense of what a life form would look like. What better, then, than something we are incapable of visualising, something even a writer of Lovecraft’s gifts could never describe? His monster is “no fruit of such worlds and suns as shine on the telescopes and photographic plates of our observatories”, but “just a colour out of space – a frightful messenger from unformed realms of infinity beyond all Nature as we know it”.

Perhaps the true horror in Lovecraft’s tale lies in the thought that there might be things we cannot imagine. At the end of the story, the alien colour shoots off into the heavens, leaving death and devastation in its wake. But a witness sees a fragment of the colour sink back into the Earth – and knowing the unearthly hue still remains, “he has never been quite right since”.