No one can really know how much time they have left to live, though some have a better idea than others – the terminally ill, those about to attempt suicide, or those who are under heavy fire, for example. The rest of us, if we don’t just ignore the ticking clock, may from time to time do a little best-case scenario calculation. I do. I am 56 now, so I have at best another 30 years of life of a reasonable quality, probably fewer given my father died from heart problems at 70 and my mother had dementia in her early 80s. Some projects, like writing books, take a long time – more than a year if there aren’t any distractions, probably much longer, so I know I won’t be writing many more of them, if any. I’d like to see how my children’s lives go, and spend time with them at the different stages in their life, but there’s no guarantee I’ll get to see them middle-aged. Nor can I be sure I’ll get to spend as much time with friends and close family as I expect to – already several have died unexpectedly. I might be next; or they might be.

This is all obvious. The experience of time speeding up the older we get is something of a cliché too, but still accurate. I remember when I was ten watching the droplets of rain crawling down the window and feeling that wet Sunday afternoons stretched time. They did: the intense grey tedium of life in the pre-digital suburbs, when there was nothing to do, is scarcely imaginable today. Time passed more slowly then. In contrast, the years from the birth of my first child (twenty-three years ago) until now went by in a blur. Some childhood Sundays seemed to have taken up more time than that.

Philosophers have often told us that it is the brevity of life that gives it meaning, because if it just went on and on we wouldn’t have much reason to do anything at all, and eventually everything would seem tedious and pointless. That – if true – is some consolation when thinking abstractly about death. Yet most of us feel we could do with just a bit more, a bit more quality time, a few more years in good health to do the things we really want to do.

The Roman philosopher Seneca had some good advice in response to those who worry about the brevity of life. In his essay on the topic, he suggests that the problem isn’t that life is short, it is that most people simply fritter it away. Specifically, we allow other people to steal our time. We make life seem short by allowing them to eat away at our precious hours as if they were nothing to us or were replaceable. It’s a kind of intellectual blind spot. We wouldn’t let other people walk off with our material possessions, but when it comes to minutes, hours – even days – it’s a different matter. Whole days of our life are stolen from under our noses. Seneca was surely right about this.

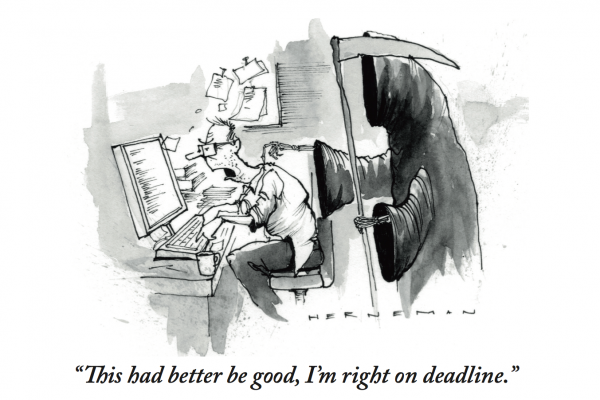

Perhaps the most efficient way of killing time yet devised by humanity is the unnecessary or prolonged work meeting. The ‘stand-up’ meeting, where all participants remain on their feet, was devised to stop these dragging on and on – though it is not fair on those with bad backs or weak knees, and hasn’t really caught on. When I was a member of a board, I suggested we should all be issued with chess clocks and allocated a maximum number of minutes to speak per meeting. My fellow board members thought I was joking. Smartphones eat time too, of course. In fact, they’re voracious. We are always available via email and apps, and the psychological rewards of another click or view are always in our pocket, wherever we are. There are benefits to this too, of course, but it is not clear they always, or even often, outweigh the costs. Only the (slightly smug) digitally-disciplined, who batch their communications and searches, escape the heavy cognitive costs of multitasking. I admit I’m not one of these, and find consolation in the stories of how connections on social media lead to new opportunities (which they can do), but it is also true that on my deathbed I’m not going to look back on my time online as the best hours of my life. Nevertheless, I find myself grazing on my messages and alerts throughout the day. I’m a helpless addict, and still that sand is going through the hourglass.

Recognising that it’s all going to be over comparatively soon, probably with a steep decline in possibilities and faculties towards the end, should galvanise us all into action. That’s certainly what Seneca and other Stoics believed. They felt that reflecting on your own death and how imminent it could be would focus you on getting important things done. And when I think about time running out, I certainly do have a nagging feeling that I should spend more time with the people I really care about, deal with my social media habit, get focused, knuckle down, finally decide what I want to do with what remains of my life and then do it with ruthless efficiency before it is too late. I could be of much more use to the world and to those close to me if I wasn’t so easily distracted and unfocused. I could be better in everything I do. But, perhaps perversely, thinking of time running out often has the opposite effect on me. I don’t do the things I know I should do, I pick up my guitar and put it down two hours later. I find myself daydreaming in a café. I go into a bookshop and start reading something that has nothing to do with what I’m working on. Everything I feel I should really have done remains undone, and the act of reflecting on time’s wingèd chariot drawing near shifts me to a different state of mind, one where ‘getting things done’ seems altogether less important than it did before.