There were scripts I learned very early while growing up in an African-American community in the urban South. In the 1960s and ‘70s, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson taught us to say, “I am somebody!”, “Speak truth to power”, and “Black is beautiful”, which still rang loud in the streets way after the black power movement and the political prisoners it created were long gone.

My mother, instructing me from a wheelchair that appeared more like a mobile throne, taught me to proudly say, “Trust yourself” and “I can do anything anyone else can do”. These were words I knew. Like the words of the god of the black church, they were to be written on my heart, engraved there to give me power when I felt that same heart was failing me.

I thought these words were part of a monologue – something I was supposed to say to myself. As I grew older, I realised they were also meant to be spoken in response to other voices. My lines were part of a dialogue. No one-woman show here! I was part of a larger theatric production called Life. And in Life, the stage is more elaborate; the plot is more intense; the stakes are much higher; and the actors are loud, rude, and manipulative (at least some of them are). So, when the drama comes, and if we are to survive and thrive in pursuit of peace, love, and justice, we’d better remember our lines and pay close attention to the lines directed at us.

ACTOR

You are not a human being!

YOU

(Confidently) I am somebody!

The actors’ lines I am concerned with are not as explicit and therefore not as easy to detect as the example above. They are more subtle, more persuasive. Their words can make even the strongest among us doubt her value and voice. They can also make you feel guilty for speaking freely and empathising with the unfree. Their lines are often uttered under a soft score of confidence and reason – reportedly orchestrated in the spirit of objectivity – to not only prevent you from questioning them, but to seduce you into questioning (and not in the Socratic sense) yourself and others you are in solidarity with.

These actors get audience uptake in ways that so many others, particularly members of minority communities, do not. They also receive a certain level of applause that is jarring to anyone committed to truth, justice, and morality.

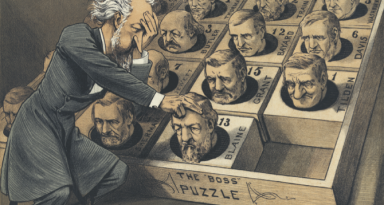

The aim of their dialogue is to disempower – proving that destructive power is not only exercised through nuclear weapons or colonial domination but through the words of everyday people. This is Power 2.0. Intention doesn’t matter. The script, along with its perlocutionary effects, silences and disempowers others.

However, like all abusive power, it must be recognised and challenged. And if “knowledge is power” then a copy of their character profiles – including when they are likely to speak and the discursive moves they are likely to make – is helpful.

Let me set the scene.

You articulate a ‘particular’ problem or praise a particular exemplar.

(Enter the Universal Actor)

The universal actor’s role is to universalise anything that is particular. He often responds to your “black lives matter” with “all lives matter”, or “all women are oppressed” with “all people are oppressed”. He universalises in order to obscure reality. Drawing attention to the particular is self-incriminating so he universalises in order to implicate everyone. This saves him from taking responsibility. In the context of praise, he also universalises to centre himself. It saves him from having to acknowledge the achievements of specific individuals by drawing attention to everyone (which includes himself). He is that insecure. His timing is strategic and he is often disingenuous.

You claim that a particular action

is wrong.

(Enter the Nuance Actor)

For the nuance actor, everything is so much more complicated than you can imagine. Although you believe you have made a proper moral claim, she questions the extent to which you have looked at all sides. The nuance actor’s job is to silence your criticism. Nothing is ever what it seems (or so she says). Her response to you speaking out against any act of injustice is always: “You can’t make a judgement right now.” She will invite you to engage in conversations to discuss this complexity as a way to halt simple action.

You report a wrongdoing.

(Enter the Gaslighting Actor)

The gaslighting actor’s role is to say whatever she can to get you to incorrectly question and doubt what you have reported. You might tell her about an injustice you have experienced. Instead of listening or giving you the benefit of the doubt, she makes you doubt your experience. “Don’t be so emotional,” she says. “He didn’t mean it like that.” You might tell her you were assaulted. Her response is likely to be, “Are you sure that’s what happened? He is such a good guy.” The gaslighter often appeals to your social position as a reason to doubt your experience. Perhaps you fail to have a proper understanding of what “really happened” because you are an “angry brown man”, “it’s that time of the month”, or “your English isn’t that good”.

You hold someone accountable for their racist actions.

(Enter the Fragility Actor)

The fragility actor is a defensive person. Because he is not used to being put in situations in which he has to talk about race or question his own complicity in racism, he is likely to get stressed. In response, he puts up defensive mechanisms to escape the encounter. His best weapon is tears. He cries to get supporting actors to come to his aid. This is strategic. The plan is to interrupt your speech and take the focus away from your concerns and criticisms. He is used to making himself the centre of attention. He is not used to being challenged. In response to your words he will say that you are the bad guy. The redemption of his image is what he craves.

Curtain

It is so easy to fall under the discursive power of universal, nuance, gaslighting, and fragility actors, particularly when they disguise themselves as friends instead of foes. They are on stage to make you edit your affirmations, doubt yourself, unfairly question your judgements, and leave you silent and eventually invisible and powerless. Knowing how they operate is useful for making sure they do not catch you off guard.

Being in dialogue with others is a beautiful thing. But when anyone uses dialogue as a smokescreen for domination and not exchange, recognise it for what it is, clear your throat, and continue to say your lines.

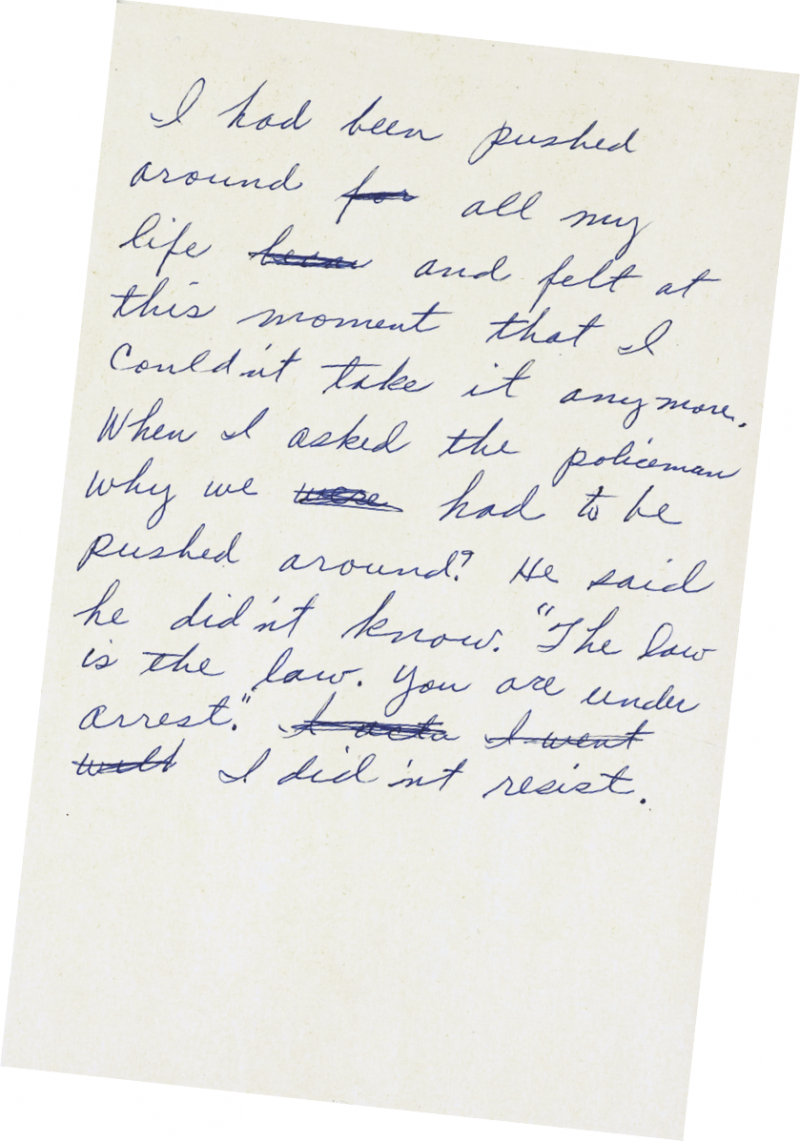

Rosa Parks Papers: Writings, Notes, and Statements, 1956-1998, Library of Congress