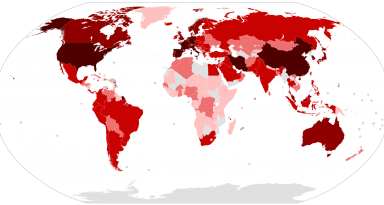

We are publishing submissions about the COVID-19 crisis from readers daily on NewPhilosopher.com in the hope that it can help us all make sense of what is happening, and as a historical record of how it made us feel. Here are your thoughts, from around the world.

By Poppy Wood, England

Lockdowns are nothing novel in literature. And for good reason — there’s something romantic about being holed up inside on a hot day. The pent up energy. Characters bubbling on the event horizon, until frustration bears its fruit.

Curiously, being locked up in a house somewhere in Britain is a trope often afforded to children in literature — a way to portray the boredom that comes with youth. In Ian McEwan’s Atonement, children loll about a grand English country house, throwing balls against the William Morris, watching flies buzz about window panes as summer light streams in. Leo Colston in LP Hartley’s The Go-Between is on the cusp of adolescence, his pubescence fizzing between the walls of a Norfolk estate. In CS Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the Pevensie siblings, bored and restless after being exiled during the Blitz, enfold themselves in the nooks and crannies of a country house, its “long passages and rows of doors leading into empty rooms”.

Looming large in all such novels is the sense of a world outside — the sense that these children are being locked away from the playing field, blinkered to the world’s stage. In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, this stage is the Second World War — parents at home in London, men on the battlefields. In both Atonement and The Go-Between, the outside world is the world of adulthood — a world where sexual tension simmers slowly towards boiling point, of people weaving out of childhood rooms and into hedges, slipping past locked doors, of notes being passed through fields.

The result in each of these three books is a sense of longing, borne out of closed systems and shut-off rooms. These children are desperate to join the race, to belong to the worlds they can spy through the cracks. In modern terms, these children experience the fear of missing out — Fomo, as we might call it in a more digital lexicon. The events of the novels are, by and large, reactions to this feeling, attempts to redress the power imbalance that comes with age difference. The children use their imaginations to either escape from the worlds they are shut out of, or to effect change within them. Briony Tallis fibs her way into relevance in Atonement, shifting her role from peeping Tom to protagonist, irreparably changing the course of many lives in the process. 13-year-old Leo becomes the eponymous Go-Between, blotting his moral compass on the letters he passes between Ted and Marian. The Pevensies, literally or not, slip into a world of pure fantasy — of talking beavers and centaurs, where the children themselves rule the land.

The difference between the locked English houses of these three novels and the current lockdown, imposed by Prime Minister Boris Johnson to curb the spread of coronavirus, is that right now there is no world outside. There are no men on the battlefields, or Cecilias weaving through hedges. Everybody — or almost everybody — is locked indoors. The only calls to arms are for the NHS, the only notes being passed are Preferred Delivery Locations. There is no fear of missing out, because there’s nothing to miss out on — most people aren’t going anywhere. Life as we know it is on hold — as Johnson himself put it, “like putting your laptop to sleep for a while”. For perhaps the first time in living history, then, the boredom of children exists on the same plane as the boredom of adults. Across the country, children are throwing tennis balls against walls, watching moths flock to the light, counting tiles. But so too are adults.

But there are technological differences, you might say. Adults have smartphones and laptops and video conferencing. Indeed, for the first week under lockdown, friends of mine clocked onto social media every night, sent a million messages, trawled through memes. But as the second week of lockdown bobs onto the horizon, people have started to switch off, put limits on their video streaming time. The race to be A Somebody is off, if only for a moment — the boredom of Briony and Leo and the Pevensies is slowly oozing up the generational chart. People are purely being — being bored, like children. And this is something to be glad about.

Boredom is exceptionally important. It fosters a sense of imagination; of real, genuine thought. Being locked inside for a long period curdles time — days seem both long and slow, waxing and waning in a peculiar way. Over time, we lose the veil of activity that comes with routine, and start to create private worlds. In the Pevensies’ landscape, the world of the wardrobe exists on a different timescale. Days in Narnia are mere minutes in the real world. In delving into their imaginations, the children literally warp time — they manipulate it, fill the gaps between meals so that they burst with narrative. Briony, meanwhile, erects her own pillars within the architecture of the Tallis house. She plays with dolls houses, imagines herself as a troubled Arabella, and forces her cousins to stage her whimsical plays. Synecdoche fragments the timescale in Atonement, one that stretches out of a childish imagination and creeps into the British countryside. These novels all take place within this fermented dimension because it acts as a world unto itself — a cocoon-like plane where personalities slowly calcify.

“Interior lives”, as literary critic Richard Schickel called it, a term handed down from Catholic mysticism to refer to the inner universe one creates when faced with a monastic existence. All over the land, people will be eating crackers cramped, sticking necks out windows, locking bathroom doors — and with no space to go, people might just look inside themselves for some. We have been handed a strange bubble of time with this crisis — one that we are only just at the beginning of — as if, like children, we have been sent to our rooms to think. Imagination is something rarified in our modern society — stamped out by the more monetizable mindfulness and the strive towards self-optimization. If anything good comes from coronavirus, it will be the return to imagination; the pure childish pleasure of sitting, staring at a wall, and thinking.