By Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore

Last year my 92-year-old grandmother, April, wrote a letter to The Times of London:

“Sir, Why do we have to announce, in death notices, that all our loved ones have died ‘peacefully’? Why can’t we be a little more realistic and honest? Why not die gratefully, reluctantly, joyfully, dreamily, gently, lingeringly, longingly, lovingly, defiantly, furiously, humorously, enigmatically, cheerfully, jauntily, hopefully, or bravely? At least more meaningfully.”

April – a former actress turned author, with a nipped-in waist and dark hair who, to this day, remains upbeat and glamorous – has seen a fair amount of death. She survived World War II in England, feeling a pang of guilt as Jews like her were murdered in Europe. More recently, her friends and loved ones have started to pass away. They include my grandfather, with whom she shared 62 happy years of marriage before he died aged 87.

Now, as she approaches her mid- 90s, she has declared that when she is ready, too, to die, she expects to be “taken to Switzerland”. But not – she instructs, with a stern face and a look of horror – before she has finished her book. (She would hate to go without knowing how it ends.)

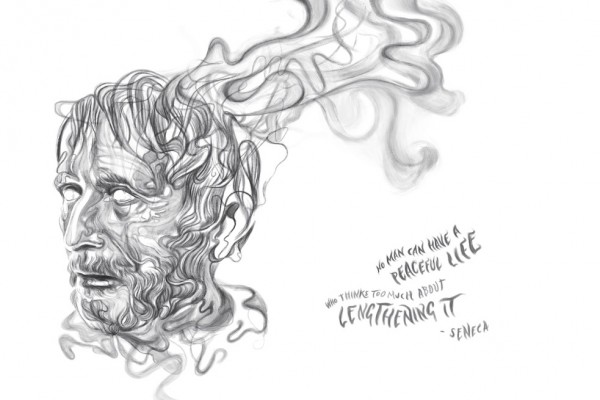

Death is, of course, the only certainty in life: just as we are born, we will die. But the question of what makes a good death is much more complicated.

For April, it is control, as well as some honesty around what death means. For my grandfather, Stephen, a good death was remaining cognisant (my last memory of him is of a man, suddenly very old and very thin, but with a twinkle in his eye even then, holding a great history tome on his lap). A good death, too, was the knowledge that his body would be donated to medical science, so that other young trainee doctors, as he once was, could learn from his limbs, and brain, and heart.

Mitch Albom wrote in his hit book Tuesdays with Morrie: “The truth is, once you learn how to die, you learn how to live.” But such proclamations are romantic. Death, even for those at peace, is rarely painless. Death is demanding physically. My grandfather was ready to go – he had a long marriage, a meaningful career, four children, and legions of grandchildren. He had travelled the world, added significantly to the art of psychiatry, his field, and learned to love the small things, like a crisp morning walk in the countryside.

And still death did not treat him kindly. When he finally passed away, surrounded by family, his body struggled, until the end, to stay. His limbs convulsed and his eyes jerked; his organs refused to give up. Whereas once a kindly doctor might have eased him into death with a sudden uptake of morphine, in today’s world of lawsuits and legal action such a step was impossible.

There is a reason why ‘death’ is traditionally dubbed the Grim Reaper – a ghoulish skeleton who wears a black hood and carries a scythe.

For many, particularly in this secular age when many consider the afterlife a fanciful myth, there is the fear of nothing to contend with, what Philip Larkin called:

The total emptiness for ever, The sure extinction that we travel to And shall be lost in always.

For others, it is the distress as we transition. “I am not afraid of dying, I just don’t want to be there when it happens,” quipped Woody Allen.

Indeed, most of us can think of a thousand ways to have a bad death: a plane crash, a fire; being bludgeoned, stabbed, or strangled; crushed, battered, or drowned.

But what makes a good death is more contested. Is it euthanasia, the option to choose the when and the how? Is it dying in your sleep? Is it dying with time to spare? Time to say your goodbyes, to pay your debts, to mend your regrets, to make peace? Or is it dying suddenly? Is there comfort in what is mercifully quick? “She died instantly,” they murmur as reassurance. “She would never have known.”

Or, like Adolf Frederick, the 18th century King of Sweden, is it dying doing something you love? He allegedly ate himself to oblivion in 1771 at a feast in which he devoured – among other things – lobster, kippers, caviar, champagne, and 14 bowls of selma, a hot milk dessert.

Ian Cognito, a respected 60-yearold British comedian, made headlines when he suffered a heart attack, dying on stage during his own set in front of a confused audience. A few minutes earlier he had joked, presciently, “Imagine if I died in front of you lot here.” One friend told the BBC it was the way he “would have wanted to go… except he’d want more money and a bigger venue”.

Then there are those who give up their lives for a larger cause. Nietzsche once said: “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.” Perhaps the same is true of death: the samurai who commits harakiri (ritual suicide by disembowelment) to preserve his honour, or the Japanese kamikaze pilot who blows himself up for the good of the nation. The people of Masada, the mountaintop fort in Israel, who, the story goes, killed themselves – the children first, then women, and finally the men – rather than submit to Roman rule.

Grace and humour in the face of death is also highly valued. According to legend, when Saint Lawrence (disturbingly the patron saint of cooks) was roasted alive, he told his executioners: “Turn me over – I’m done on this side.”

In the western world today, however, the vast majority of people will die of heart disease or a stroke (combined, they accounted for 15.2 million deaths in 2016). Death for most, in this age of prolonged healthcare, won’t be violent, but slow. Almost all of us will move into the “kingdom of the sick”, as Susan Sontag called it, at some point; many will end our lives there.

Studies have shown that having control over pain relief is paramount to the dying, as is having some sort of decision-making power over where they will die (and who will be there when it happens). There is also – as my grandmother April pointed out in her letter – the war over language. What makes a good death?

This is most apparent in the way we talk about cancer. Those diagnosed are ‘brave’; the illness is often described as a ‘fight’ or a ‘battle’. The more disturbing aspects of the disease are covered up with rousing platitudes.

It isn’t helped that death remains taboo in our culture. We can talk about ‘winners’ and ‘losers’, those who ‘fought to the end’ and those who ‘never gave up’. But the realities of what death means – the thousand physical degradations, the crippling pain, the spasms, like those my grandfather suffered – are rarely discussed.

And what about the mental agony? In his book, When Breath Becomes Air, neurosurgeon Paul Kalanithi, dying of terminal lung cancer, decided to have a baby with his wife. “Don’t you think saying goodbye to your child will make your death more painful?” she asked him. “Wouldn’t it be great if it did?” he replied, adding: “Lucy and I both felt that life wasn’t about avoiding suffering.”

In Better Off Dead, journalist Andrew Denton’s podcast on euthanasia, one episode stays with me. It is the story of Raymond Godbold, an Australian palliative care nurse facing life-ending gastro-oesophageal cancer. Aware of the physical horrors that awaited him, he secured the illegal, and deadly, drug Nembutal to take when the time came.

But then, every day, waking up to his wife and children, he couldn’t do it. He wanted one more hour with his family, one more hour to see the sun shine, one more hour to talk. And then another. And then another. And another. Eventually, he became too ill to swallow and he died the way he never wanted to: in hospital, in pain. He bargained away his ‘good death’ for time. For just one more day of life.

From the Death edition of New Philosopher, available here.