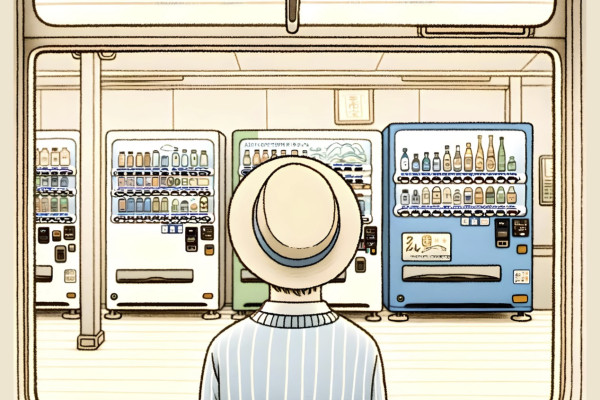

I recently visited Japan for the first time. When I got back, and people asked me what I had found most interesting or surprising, I found myself talking about small things rather than big ones: public toilets rather than temples; side streets rather than castles; vending machines rather than bullet trains. The temples and the cherry blossom were wonderful, of course. But I already had some sense of what widely-photographed world heritage sites would look like. What I hadn’t anticipated was the rows of vending machines selling gourmet dishes in spotless subway stations; the lifelike fake food and drink lined up in shop windows, plastic noodles suspended mid-slurp; the baseline of calm and quiet that made Tokyo, the largest city that has ever existed, feel less frantic than my mid-sized hometown on a Saturday night.

Among the smallest and most striking things I noticed was the conductors of inter-city trains pausing, turning, and bowing before leaving each carriage. Britain has a (mostly) decent (ish) train system, but that kind of thing doesn’t happen here. What was going on? After speaking to some Japanese friends, I found an interesting range of perspectives. First, employees are following a company rule: this isn’t a spontaneous act or personal choice. Second, it isn’t necessarily passengers who are being bowed to: respect is being shown to the job and the train as much as the people. Third, this kind of thing isn’t universal or guaranteed to continue. But it is bound up with an important idea in Japanese culture: the dignity and value of performing any given activity with excellence.

In her 1966 book Ikigai-ni-Tsuite (“About Ikigai”), the Japanese linguist, psychiatrist, and author Mieko Kamiya defines her titular concept – ikigai – as that which makes life worth living. The idea of ikigai has been important for centuries in Japan but, she noted, it’s elusive and almost impossible to translate. This is because it encompasses both the sources of meaning in someone’s life and the emotions that they experience in response. It’s also resolutely active and particular rather than abstract. Scale and impact have nothing to do with ikigai. What matters is the sense that you’re doing something worthwhile – and this sense is in turn conferred by doing it purposefully and well. To invoke a second Japanese concept, hatarakigai (“work worth doing”), neither pleasure nor monetary reward are the most important determinants of a task’s value. Excellence and social impact matter just as much.

Fittingly, Kamiya’s book itself hasn’t been translated into English: I’m basing the above on others’ analyses, and I’m sure that I’ve missed several layers of cultural nuance. As someone with an interest in western virtue ethical traditions, however, I’m struck by the common ground between ikigai and European concepts of human flourishing. From Aristotle onward, flourishing has offered a satisfyingly active metaphor for finding purpose in life. It’s something that you do – that you grow into and actively pursue – rather than find lying around inside a book. And it’s also something that you don’t wholly control. To flourish is to align your circumstances with your own nature, gifts, and limitations. It requires a degree of good fortune, self-reflection, and humility. There is no one recipe for a life worth living, or an equation capable of maximising purpose and impact. Rather, there’s the business of inhabiting your own opportunities more gratefully and deeply; of seeking out sustaining relationships and role models; and, perhaps, of becoming a role model yourself.

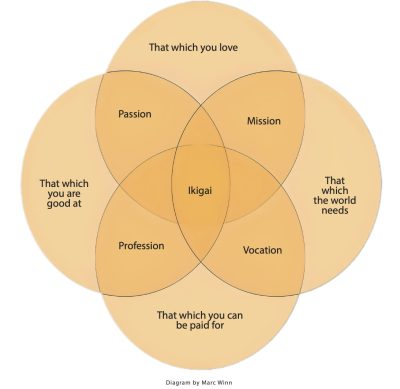

An irony of ikigai is that, for all its elusiveness, it’s best known internationally thanks to a viral Venn diagram, created by the British activist and entrepreneur Marc Winn in 2014 in response to a TED talk on longevity by the author Dan Buettner. In the diagram, ikigai exists in the intersection between four factors: that which you love, that which you’re good at, that which the world needs, and that which you can be paid for. It’s a useful model for reflecting upon your own values, talents, and routes to fulfilment – something eminently worth doing. But it’s not ikigai in the Japanese sense. Indeed, Winn’s own diagram is closely based on one created by the Spanish entrepreneur and astrologer Andrés Zuzunaga, in which the central intersection was labelled propósito, meaning “purpose” – a singular, definitive prize, worth pursuing at maximum velocity.

What connects viral Venn diagrams, train conductors, and hard-to-translate cultural concepts? One of the joys of being a tourist is becoming temporarily inexpert in life’s little rituals, and thus having to attend to them closely: how to greet people, thank them, excuse yourself, show respect. This was compounded, on our trip to Japan, by the fact that we had our eight- and ten-year-old daughter and son with us. They loved learning to say hello and express profuse gratitude in Japanese; they loved the cleanness and courtesy of the everyday. And I loved being there with them, experiencing the strangeness and newness of travel together, savouring the privilege of unstructured time.

Like most parents, I regularly feel that I am not good enough at the most important thing in my life: raising my children. Watching them show others small kindnesses, however – watching them endure long journeys, relish small differences, bounce back from inconveniences and upsets – I allowed myself to take pride in their flourishing. Part of the pain of parenting is the fact that family is never a singular focus. The rest of life is always there, demanding, competing, distracting, seducing. There is never enough time, energy or patience for everything to be done or some final excellence to be achieved. Yet it’s this tempestuous interplay between the source of meaning and my experiences of it that defines parenthood as a living, striving thing. And it’s the small rituals of respect, compassion, forgiveness, and foolishness that help me find a way forward – or find a way back when everything feels disconnected and broken.

The ideas of purpose and flourishing are intimately entwined, and for good reason. To flourish is to grow in a certain direction: to fulfil a potential, develop and exercise a skill, achieve a goal. In Japan and in ikigai, however, I’ve found a reminder that neither grandeur nor singleness of purpose are necessarily admirable – or what makes life worth living. One of my happiest memories of our trip is my son and daughter sitting in a tea house, ordering bowls of noodles and sipping tea, looking at a beautiful view. Not much happened, except that they embraced the moment alongside us, proud we’d climbed together to that spot. The noodles were excellent, the tea fresh and hot, the city beneath us buzzing with life. It was enough.

From the 'Flourishing' edition of New Philosopher, which you can purchase in digital or print editions from our online store.