Interview by NP's editor Zan Boag with Angie Hobbs, Professor of the Public Understanding of Philosophy at the University of Sheffield. Her chief interests are in ancient philosophy and literature, and in ethics and political theory from classical thought to the present; and she has published widely in these areas, including Plato and the Hero. Her most recent publication for a general audience is Plato’s Republic: a Ladybird Expert Book. She contributes regularly to radio and TV programs and other media, including 25 appearances on In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg. Hobbs lectures and gives talks around the world: she has spoken at the World Economic Forum at Davos, the Houses of Parliament, the Scottish Parliament, Westminster Abbey, and the United States Air Force Training Academy in Colorado. She has been the guest on Desert Island Discs, Private Passions, and Test Match Special. She was a judge of the Man Booker International Prize 2019 and was on the World Economic Forum Global Future Council 2018-19 for Values, Ethics and Innovation.

Zan Boag: You’re quoted as saying that you believe eudaimonia to be a hugely important and helpful concept, maybe even the most important concept that should be taught to people. Why is it so important, and how do you teach it to others?

Angie Hobbs: Okay, let’s break that down into the two parts. The reason I really like eudaimonia, which in ancient Greek literally just means, “looked after by a beneficent guardian spirit”, is because it’s a more objective concept than happiness, or pleasure. It’s much more to do with the fulfilment of your faculties, the actualisation of your potential, living a rich and fully human life. And it’s something you can hang on to even in circumstances where feeling happy just isn’t possible, let alone feeling pleasure.

You can’t always feel happy. Awful things happen in life. You can’t feel happy every moment or indeed every day. And sometimes it would just be insensitive: imagine if I went and turned on the TV and saw the destruction of some civilian population in Ukraine or elsewhere, and just laughed merrily.

The fulfilment of your faculties provides a solid framework. Of course, over time and place, the canvas will change, the picture will change, but you’ve got a solid frame. Other ethical approaches such as consequentialism or deontology rights-based and duty-based ethics are act-centred, but I prefer an agent-centred ethics, which starts with these two really basic questions: “How should I live?” and “What sort of person should I be?”. You don’t initially have to be committed to virtue or morality to care about those questions.

I really like the fact that it’s about the whole person living a whole life. It prompts you to ask questions about the shape of your life, the style of your life, the narrative of your life. And that brings us very quickly to relations between ethics and aesthetics – something which really appeals to me. But it also gets you asking immediately, “Well, OK, this is about my flourishing, but what kind of infrastructure needs to be in place socially, politically, in my community for me to flourish?” Very minimally, don’t I need access to healthy food and clean air and water and housing and so on, and job opportunities and cultural and leisure opportunities too?

The links between ethics and aesthetics, the links between ethics and political and social theory and practice are immediately foregrounded. And so, for me, it’s an ethic which is sensitive to the complexities of the lived human experience. And I find that very user-friendly. Your next question was: “How do you teach it?” Well, I think I would go at this in two ways. I would say from quite a young age, really still in primary school, you can start to get children to think about what they think a good life is and what it involves, and also then what kinds of qualities, what kinds of excellences and skills, and what kind of support system are needed to make that good life possible, both for the individual and the community. You can get quite young children to start to reflect on these issues and ask questions.

But also, and this is something which is a real passion of mine, I think it is vital not just to get children to think about a good life, but also to enable them actually to live it. I’m really passionate that school should not just be about preparing children and young people for adulthood – very important though that is – but also be about giving children a chance to flourish as children, because these years form a significant part of any person’s life. And for a few children, tragically, their school years are the whole of their lives, so we absolutely owe it to children that these years should be years of flourishing in themselves – full, rich years in which their various intellectual and emotional and physical capabilities are given a chance to be exercised.

I think I first started to think about flourishing – rather than feeling happy or feeling pleasure – when I was about 19 and first came across Nozick’s Anarchy, State, and Utopia, and the “pleasure machine” experiment: if someone offered to plug you into a machine that could make you feel pleasurable sensations for evermore, would you accept? You are assured that once you’d been plugged in, you would never regret it, but still, as you are now in your current state, would you agree? And I knew that I wouldn’t.

And then I thought, well, supposing it’s not a pleasure machine, but a happiness machine. If I knew I could be plugged into a machine where I would feel happy and content forever as a subjective state, again, would I do it? And again, no, I wouldn’t. I wouldn’t want to turn on the news and smile happily at the sight of innocent civilians around the world being destroyed. So Nozick got me started.

And then, at university, I discovered Plato. Although my political views are very different from a lot of what the character Socrates says in The Republic, for instance, nevertheless Plato really resonated with me. He is a great artist as well as a great philosopher – and of course he never speaks in his own voice, so we can never be entirely sure whether he agrees with what the character of Socrates is saying. In the Gorgias, the character of Callicles starts off claiming confidently that the good is unqualified pleasure, but then through careful question and answer, Socrates gets him to agree that actually he doesn’t think all pleasures are equally good. He hates cowardly pleasures, for example – he admires the ruthlessly strong and capable man of action. While I certainly don’t agree with Callicles’ views either, Socrates’ conversation with him again convinces me that unqualified pleasure is not the good.

So, from my late teens, I have felt that a good life was a rich, fully human life in which all my capacities were being exercised, including my capacity for feeling sad when that was appropriate, for feeling pain when that was appropriate, for empathising with the pain of others. I don’t want to be endlessly cheerful and not respond to other people’s pain.

It’s interesting you talk about education and the years when children are at school. I think in the modern world we face a raft of challenges in that the formal education system isn’t the only way children are being educated. There is a plethora of other means by which they’re being educated, whether that’s through online media, through television or online videos or whatever else it may be; through their interaction with their peers on social media, and so on. I think there was a time where the education system was perhaps the primary way children learnt how to behave and what was a good life. Now they’re learning a whole range of other options for what a ‘good life’ might look like. And I think an issue with this is that the ‘good life’ that’s presented to them through the media tends to be one that is not necessarily what will be a good life for them. It’s a good life for the companies if you buy their products perhaps, but maybe not a good life for these children. How can this be countered?

That’s such a good question. You use the phrase “the good life” at one point there and then you change to “a good life”. And I would very much want to stick with “a good life” as we go on – unless we are specifically discussing the views of philosophers who use the singular. I want to resist ancient Greek notions of the one ideal good life, which most of us will inevitably fail to reach. A good life. But you are right – they see a range of purportedly good lives on offer, and a lot of them are very materialistic and all about the consumption and display of material goods as a sign of success. Until social media platforms achieve the status of publishing platforms under editorial control, we have very little influence over that. And they’re a mess at the moment, I agree.

We have to go at this another way. This is another reason I’m so passionate about philosophy in schools from really quite a young age. Unexamined extracurricular philosophy classes from as young as six, seven, eight – ‘unexamined’ because when Socrates said that the unexamined life is not worth living, he was not advocating the relentless testing of very young children... This would help give them both the critical thinking and reflective skills and also the creative and imaginative skills needed to assess the influx of material they’re getting through the media, social media, their friends. It’s not going to be perfect. We won’t have complete control over this, but there is the chance of progress. We don’t have to resign ourselves to the current wild west situation – it’s not hopeless. And in my experience, young kids and teenage kids are often more savvy about cutting through the nonsense than older people.

Potentially they’re presented with so many different ideas that they’re actually learning, in some respects, quite deep ethical thinking at a young age. They’re learning about the ways of the world at a much earlier age than I did, for example.

Yes, I think that’s right. And it’s interesting. I get parents, grandparents, teachers writing to me – and some young people, I am happy to say. I also get librarians writing to me. I think librarians are an underused resource in this project of helping children to become digitally literate. There are lots of people out there wanting to help, with resources to help, and we need to progress. We can’t fix things completely, but we can make quite a lot of progress.

I’d like to just skip ahead beyond children and beyond the education system to adults – what it is that we can do to increase our chances of flourishing. In an interview some years back, you spoke about how the ancient Greek city state was constituted by overlapping circles of friendship, and that friendship was “a necessary constituent of a flourishing life”. I think a lot of people would agree with that idea. Aristotle went as far as to say that we need friendship to actualise our faculties, to be fully human. I’d like to know what you think of this idea, but also how friendship has changed, and whether it is a little bit more difficult for us to have these circles of friendship in the same way that was possible in the city-state back in Athens?

Let’s start with Aristotle and then move on to the current day. We tend to get very nervous when Aristotle says he wants overlapping circles of friendship to be the building blocks of the state – we rightly get concerned about issues to do with nepotism and corruption. There is clearly the potential for problems here. However, there’s also a lot we can learn from, I think. Let’s look at why Aristotle in the Nicomachean Ethics, and indeed Plato before him, for example in the Lysis, think that friendship is so crucial to a flourishing life. Firstly, they just think it’s a constituent of a good life – they would say the good life – we’ll come back to that – in itself; it’s just one of the pleasures of life. And they also think that friendship is vital for the state. Aristotle says friendship forms the relationships of trust, which he says are the building blocks of the state – relationships we are sadly lacking in at the moment. But also both Plato and Aristotle say you need friendship to acquire and display certain moral and intellectual virtues or excellences – the Greek aretē really just means “excellence”, and that term may be less off-putting to some. And they both argue that exercising our capacities for moral and intellectual excellence is intrinsic to the – singular for them! – good life.

For example, to acquire and display justice and generosity we need to be based in a community. And if we have good friendly relations with people in that community, then both the acquisition and the practice are going to be easier. As for the intellectual excellences, though both Plato and Aristotle think at the final stages of philosophic ascent, we can practise them by ourselves, at least for a little bit, they both think that early on you need to do philosophy with other people, in dialogue and debate. Aristotle says explicitly towards the end of the Ethics that though the perfect human could do philosophy by themselves, we’re frail mortals, and we don’t really have the stamina and energy to keep going for long alone: we need a community of friends. Plato doesn’t say that outright, but he certainly implies it in the fact that he writes dialogues – he always shows Socrates or another main interlocutor having discussions with groups, or at least one other person. You can of course have discussions with people who are hostile to you, and we see Socrates doing that with Calicles in the Gorgias and with Thrasymachus in Book 1 of the Republic, but you’re usually going to have a much more productive philosophical discussion if you’re all doing it in a collaborative and friendly spirit.

So both as a constituent of the – as they would term it – good life and also for the acquisition and display of moral and intellectual virtues, both Plato and Aristotle think that friendship is profoundly important. As we have seen, this is certainly not problem-free – during the pandemic many of us around the world saw politicians offering mates’ rates to friends who were not always the best qualified to provide PPE, for instance. But though Plato’s and Aristotle’s thoughts on friendship raise issues, they are still really interesting and worth considering.

In respect of your second question about the problems with friendship now, I still think it’s really useful to look at Plato and Aristotle for guidance because they both think there are three different types of friendship. Plato talks in the Lysis about, firstly, friendship with opposites and then, secondly, friendships with people who are like you. However, he says that the very best kind of friendship is when a good person is friends with another good person for the other person’s sake, because they are simply delighting and rejoicing in the other person’s goodness and wishing them well. Aristotle also analyses friendship into three basic kinds, although his first two are rather different: utility friendships, and friendships based on shared interests, such sporting interests. But he then agrees with Plato that the best kind of friendship is when a good person is friends with another good person for the other person’s sake, because they are delighting in their goodness. I think both of these accounts are helpful lenses through which to look at current challenges to friendship. When I read that some celebrity has invited 2,000 “close friends” to their 50th birthday party… nonsense, nobody has 2,000 close friends! Maybe 10 to 20 really good friends, but maybe only five, or fewer than five, friends who you really could ring up at 3:00 in the morning and they would drive several hundred miles to help you out.

In my view, I think friendships are usually best started face-to-face. You can then continue them online of course. I am certainly not dismissive of online communities – they were vital in the pandemic, and for people who are neurodiverse or suffer from agoraphobia, they can literally be a lifesaver. So I’m definitely not opposed to them, but I think in most cases it’s best if you start the relationship face-to-face – you can just pick up so much more from the body language, and simply sharing the same physical space is, I think, very important. And then continue the friendship both in person and online.

I’d like to stay on friendship – you mentioned earlier about the Greek notion of ethics, how one should live, who one should be. I just wonder where a friendship fits in here, in that friendship offers the opportunity to hold a mirror up to yourself: how you are living and how you behave. How important is this role of friendship in holding a mirror up to your own behaviour, your own ethics, and the way you live your life?

That’s so interesting. Both Plato and Aristotle say that about friends. And Plato also says it about erotic lovers in the Phaedrus, you’ve got this notion of a mirror, in which you can see yourself reflected and come to understand yourself better. In fact, it can be even more effective than looking in an actual mirror, where we can focus on just what we want to see. Furthermore, they are both clear that a true friend, a real friend, should tell you when they think you are going off course. And you should also do that if you are a real friend, whether it’s to an individual or your organisation or your country – you should have the courage to tell them, kindly but clearly, if you think they’re making real mistakes.

Something I’ve been thinking about quite a bit recently is that Elon Musk said publicly that one of his children is on the spectrum and was struggling to make friends, and he wanted an AI system to be a friend for his lonely child, or the child he perceived to be lonely. There’s a really interesting question about whether we can be friends with non-humans and with AI systems. It’s tricky, isn’t it? Because in terms of Plato and Aristotle saying that the highest form of friendship is when a good person rejoices in the other person’s goodness for their own sake and wishes them well for their own sake, I don’t think that can happen at the moment with an AI system. And at the moment, as far as we know, an AI system can’t feel those emotions of affection and care for you. The AI system may display, I won’t say behaviours, may display activities which suggest they feel emotion and care, but as far as we know at the moment, they can’t.

And even if they ever developed the capacity to feel emotion and care – which would be a really interesting ethical moment for humanity about how we treat AI systems – if they ever developed the capacity to feel, I don’t know how we could know that they could feel. It’s really tricky. At the moment, it looks as if an AI system could only fulfil Aristotle’s utility friendship at best and function as a kind of training for higher forms of friendship, rather like a child has a toy and learns how to look after a person by looking after their toy and putting the toy to bed and feeding the toy and so on. I also worry that time spent with AI systems, and online friendships in general, might be time better spent developing real friendships with humans face-to-face.

It’s interesting you mentioned both AI and also online friendships, because I wanted to ask you how much the notion of individual flourishing and living a good life has changed since Ancient Greece? Potentially a lot of this change has been quite recent because of the different influences that we now have. Our concept of what it means to flourish, I think, in contemporary society is fundamentally different to what it was in Ancient Greece. I think a lot of the influences that we now have mean that our concept of flourishing has shifted somewhat. What do you think of that idea? Is it possible in contemporary society to flourish in the same way as was proposed to live a good life in Ancient Greece?

Okay, great. Let’s divide that question into two, about issues that there are with Plato’s and Aristotle’s definition of what, in their view, is the – rather than ‘a’ – good life, and why we might have problems with that. And then we’ll go on to look at the different influences now and how the content might have changed.

I think there are ways in which we really wouldn’t want to replicate their notion of the good life. They both have a notion of one ideal human life, and a hierarchy beneath it. And most of us fail and can’t get to the top. That’s because, for Plato, his notion of flourishing is to do with the harmonisation of what he says are the three different faculties of the psyche: reason, a spirited element, and our appetites, each faculty with its own desires – reason for truth and reality; the spirited element for honour, respect and success; and the appetites for food, drink, sex and the money that may be needed to acquire them.

Reason should be in control and should decide which are the best and healthiest of the other desires to fulfil. Aristotle also offers an objective account of flourishing constituted by the proper functioning of a tripartite psyche – in his case, the three psychic faculties, or ‘parts’ are rather different from those of Plato, but he agrees that reason should be in control and select which are the best and the healthiest desires to fulfil. It is this proper fulfilment, or actualisation, of the capabilities of the psyche which constitutes flourishing for him and is our human goal, or telos. So although there are differences between Plato’s and Aristotle’s accounts, they both propose a single hierarchy, and they both, very regrettably, think that mentally and physically disabled people either don’t possess all the requisite faculties to fulfil or can’t fulfil them adequately. So they think that disabled people cannot reach very high up on this hierarchy.

Aristotle also claims that women cannot reach the pinnacle. He allows that women possess reason, but says it’s not active in us because we are too emotional. If he had known about hormones, he would have said we were too hormonal. And Aristotle unfortunately also believes that there are ‘natural’ slaves, that there are some humans who simply don’t possess sufficient reasoning ability to run their own lives well and are better off if other – ideally beneficent – people run their lives for them. I of course want to protest against this too. I want to get rid of the notion of the good life, a single ideal out of reach of most of us. I want to talk about a good life, a range of good lives which are specific to the individual, particular capabilities of that individual person.

So you don’t get disabled people being denied the possibility of flourishing, for instance. Flourishing will consist in the fullest actualisation of whatever capabilities we individually possess. However, and this is an important ‘however’, we will still need particular local, social, maybe political, circumstances in which to fulfil this individual actualisation.

All of us, whether disabled or not, we’re all dependent on our social and political circumstances for our flourishing – that would remain true. We all need infrastructure; we all need a support system. But it doesn’t mean that there’s just one, single goal, which most of us will fail to reach.

And there’s another, linked problem with Plato’s and Aristotle’s ethics of flourishing. If you propose a single hierarchy with the cleverest, most educated, and most rational few at the top, then this swiftly leads them to authoritarianism, paternalism – and maternalism too in Plato’s case, as he argues for Philosopher-Queens as well as Philosopher-Kings – and indeed totalitarianism. They both argue – Plato more forcibly than Aristotle, but Aristotle also tends in this direction – that those of us who can’t get to the top will be better off if these more intelligent, better educated, better qualified people run our lives for us. Again, I strongly want to protest against that too and say, “No!”

It’s quite a dangerous idea.

It’s hugely dangerous. For me, autonomy, personal agency, is absolutely crucial to living a good life. In the reworking of ancient virtue ethics and ethics of flourishing which I am trying to do, I really want to put agency and autonomy back into the picture and say that, in almost all cases, our intellectual and emotional excellences can’t really be fulfilled unless we have personal agency.

I want to get rid of the single hierarchy which underlies the path to authoritarianism. Even though I find the ethics and politics of flourishing so rich and so interesting, I accept that, historically, it’s an approach to ethics which has sometimes led down some pretty autocratic routes. I strongly want to resist those routes.

There are a couple more reasons I want us to update and modify Plato’s and Aristotle’s accounts of flourishing. As we have seen, Plato literally identifies your flourishing with your excellence, with your moral and intellectual excellence – both flourishing, eudaimonia, and excellence, aretē, are constituted by the same psychic harmony between the three faculties in your psyche. He also says in the Republic that this state of psychic harmony is a state of psychic health, which is a really interesting and influential idea. As far as we are aware, it’s the first time, in western thought at least, that this notion of mental or psychic health is used. And these passages of the Republic were a direct influence on Freud – we know that, we have evidence about that.

So it really is important, this notion of an integrated self rather than a fragmented self. We know how crucial that is in modern accounts of psychic illness. That’s great; however, the way Plato claims that this psychic harmony constitutes virtue and excellence as well as flourishing also has the potential to be really dangerous. Because if you are going to identify psychic health with virtue, that means you’re going to identify psychic illness with vice. And that is going to open the door to serious political and psychiatric abuse. Leaders can say that a dissident who is protesting against their regime is not just vicious, but also mentally ill. And that they therefore need to be taken off to a sanatorium and have a lobotomy or drug ‘therapy’ or whatever.

This is the horrific scenario Solzhenitsyn denounces, or that we see in a book and film that affected me hugely when I was growing up, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I found the performances of Jack Nicholson, Will Sampson, and others in that film very powerful and disturbing. So, yes, the notion that your flourishing and excellence are this state of interior, psychic harmony is a very rich theory, and it’s something I write about a lot. But you do need to be aware of the dangers.

Another issue arises from Plato’s claim that the spirited element of your psyche desires honour and respect and success. If that’s the case, then what’s the best way of achieving those things in your society? Would it not be to copy or emulate the behaviour of those who are already honoured and respected, the successful role models who already exist? And that can lead to quite a conservative tendency in these role model cultures, which is one of the points made about MacIntyre’s After Virtue. I don’t think MacIntyre himself necessarily wants his ideas to go down that conservative route, but there are issues and dangers, despite all the richness, and we need to be alert to them.

However, despite all these caveats, there is one enormous benefit in not just updating an ancient ethics and politics of flourishing, but also in some cases using the ancient versions. And that’s in interfaith and faith–secular dialogue. I’m agnostic myself, but I do quite a lot of work with faith communities. And I have found that if you frame the discussions around flourishing in terms of Plato or Aristotle or the Stoics or Epicureans, people can feel much safer in that space because it’s a time which obviously predates Christianity and Islam. These Classical and Hellenistic Greek thinkers don’t predate Judaism, of course, but in these periods as far as we know they didn’t really know much about Judaism and didn’t interact much with Jewish thinkers. It’s not until the turn of BCE and CE that you start to get significant interactions between Greek philosophy and Judaism. So if you frame discussions of flourishing within the context of the Classical and Hellenistic Greek thinkers, people feel they can discuss really quite profound ethical and religious questions without feeling that their own personal faith or personal identity is being threatened. So in this respect, I have found the ancient versions a really useful common resource for everyone, in addition to providing the bases for our contemporary re-workings. But when I am engaging in these interfaith and faith–secular discussions, I also then say: “OK, we’ve started the debate in this safe space, but we do need to update these ideas.”

And they are worth updating because, as we said at the beginning, one of the great advantages of focusing on flourishing rather than happiness or pleasure, it seems to me, is precisely because it is something that we can hang on to in those times when things are really challenging and uncertain. An ethics of flourishing is very helpful in good times too, of course, but it’s perhaps particularly helpful in the bad times. I wrote about it quite a lot during the pandemic, for instance, and a fair number of people got in touch with me about it. They wanted something more secure, more solid when things were so uncertain – not just in terms of how the virus was going to mutate, but the fact that we were having to deal with the pandemic at the same time as climate change, and a rise in authoritarianism around the world and great political instability. Covid-19 is now an epidemic rather than a pandemic, I believe, but obviously climate change and the rise in authoritarianism and threats to democracy are still with us.

And of course there are a number of terrible wars at the moment, and all the urgent issues over Black Lives Matter and various fights for social justice. I suppose every generation says that everything’s very turbulent in world affairs, but it really does feel that way right now. And because of the internet, we’re probably more aware than we would have been in previous centuries.

I think that’s a big part of it, it is an awareness of what’s happening around us. I suppose my question relates more directly to those events that affects us personally. These larger events, of course they have a huge effect on our lives and on the lives of those around us. But I’m thinking about that very particular event, such as a war in one’s own country or people who have completely run out of money so they’re starving or they have some sort of anxiety that is completely debilitating, or a terminal illness and they’re facing the last days of their life. In these sorts of instances, when someone is directly affected by an event of some sort, how do people find a way through? Is flourishing even relevant in these sorts of times when it’s difficult or near impossible, or is it just a matter of getting by?

Again, unless you’ve really lost every single capacity, there’s usually something you can do with your intellectual or your emotional or your imaginative or your physical faculties to make things just that tiny, tiny fraction better, both for yourself and those around you. It could be something just like holding the hand of somebody dying next to you, or making a thoughtful will or planting a tree that future generations can enjoy. There’s usually something that you can do to improve the situation, if only by a very small amount.

I’m not remotely claiming that I would rise to the challenge in really terrible circumstances. But throughout history, we have seen people behave extraordinarily well in their dying moments or in moments of deep pain and affliction and fear.

To come back to what you were talking about before when it comes to the social and political issues that we are dealing with these days – due to some of these social and political issues, I feel that perhaps the ability to flourish isn’t a level playing field. What do you think about the notion of equality of flourishing?

OK, that gets us back to our earlier discussion when I said I rejected the notion of a single hierarchy. But I also said that despite the fact I want a range of good lives and not the good life, there still needs to be an infrastructure – and that’s true for all of us, whether able-bodied or not, whatever our level of ability or whatever our gender, there needs to be a support system. Very, very few of us can flourish by ourselves. And clearly the social and political playing field is very far from level.

Plato makes the point incisively in the Republic. He says that occasionally an exceptional person may appear who can achieve excellence in adverse social and political conditions, but most of us need the right environment. He is probably thinking of Socrates as the exception, and obviously Socrates’ political community was so far from supportive that it put him to death.

Most of us, however, need considerable social support. It’s one of the reasons Plato just rips everything up in the Republic and says, “We’ve got to start again. We need a new society. We need new role models. We need new heroes. Things are too corrupt.”

Even before we consider role models and heroes, however, it’s obvious that we all need decent accommodation and warmth and clean air and water and healthy food and access to work opportunities and human contact and social and leisure opportunities and so on. And, no, these things are not remotely equally available – that’s why I want to make this distinction really clearly between a range of good lives adapted to individual capabilities and the fact that they will all still need an infrastructure in order to be realised.

We need a supportive community to fully develop and display our faculties. And in my view, although all the ancient Greek philosophers adopt an agent-centred ethics of flourishing in various ways, I think the theories of Plato and Aristotle are perhaps more capable of being updated. With the Stoics, I struggle with their belief that everything’s been providentially arranged for the best – even if things look really awful, they actually make sense, if only we could see the bigger divine plan. I think that can lead far too quickly to passivity, and not taking action. To be fair, the Modern Stoicism movement – or perhaps more accurately movements – don’t tend to focus on the providential plan. However, I still personally prefer Aristotle’s view that, no, some things should make us angry. So long as we control that anger and use it as a fuel for social change and social justice. There is clearly not even an approximation of a level playing field, and we need to work hard to improve things.

And I think it’s getting worse. I think the divergences in wealth, education, health outcomes are getting worse in many countries, including my own. And between countries the inequalities are even starker. That’s why we’re seeing such high levels of migration across the world at the moment. And why wouldn’t you, if you felt you’d been dealt a really unfair hand in life? Many migrants, of course, are genuinely under threat, genuine asylum seekers. But even if you are an economic migrant, why would you not want to seek a better life for yourself and your family? Humans have always moved; unless you come from a long line living in or near the Rift Valley, all our ancestors have moved. We’re an amazing species. Look at the people who made it to Australia and New Zealand.

This is one of the main reasons I am attracted to an ethics of flourishing – because you can transition so quickly to a politics of flourishing. Almost everyone cares about their own flourishing and wellbeing, even if they proclaim, “I’m very selfish. I’m not interested in the greater good.” I don’t mind the term ‘wellbeing’, but I prefer ‘flourishing’ because it’s active, and because it links us vividly to the natural world.

Anyway, most people care about their own flourishing or wellbeing, and then you can usually quite quickly get them to see how things like the pandemic, or climate change, show us how intimately our own flourishing is connected to that of those around us, and conditions around us. In the pandemic, unless you were going to lock yourself away in your house forever, and just have food and medicines delivered to your door, if you were ever going to go out again, then you needed to care about vaccines and treatments and the health of those around you on the tube or the train. And the quality of the air that we breathe, and of the water that we drink, are obviously being affected by climate change. Most people can very quickly come to see how their personal individual wellbeing is affected by their community and environment.

This approach to ethics, then, doesn’t start from saying “be moral”, which some people might immediately reject. It starts from something most people can agree with: “Do you personally want to live a good life?” And then you expand outwards. The notion of the expanding circle and the way the ethics of flourishing then expands to a politics of flourishing, I find very helpful and appealing.

I’d like to look at the idea of flourishing as a work in progress – something that we are continually working on. You mentioned the ever-changing conditions that we deal with, whether it’s climate change or the pandemic, or political and social unrest. There is an ever-changing environment, and we are working on our ability to flourish within these changing circumstances. My question is, are there certain conditions under which it’s more likely for us to flourish, and can we increase the likelihood of living a flourishing life?

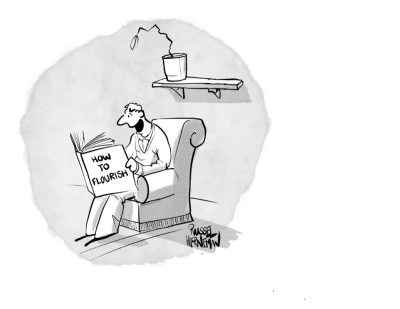

This again is another reason I am so keen on philosophy classes in schools, unexamined philosophy classes. Of course I would also like philosophy to be an examined option later, but definitely unexamined philosophy classes for all. But I am in addition a strong advocate of philosophy as a lifelong learning project – something like New Philosopher is a resource for people who want to start or continue their philosophical adventures. Because philosophy can help us to reflect on questions of what a good life might be, and what kind of qualities, skills and infrastructure might be needed to attain it.

But it can also be a constituent of a good life in itself – not a necessary or sufficient constituent, but something which can help us actualise some of our intellectual and emotional faculties. I’ve written elsewhere about how philosophy can help provide resilience and mental agility, and also creativity and imagination and empathy. All things which I think can help us develop intellectually and emotionally and in ways which will increase our chances of finding purpose and meaning in life.

There are a number of projects around the world, such as the Harvard Flourishing Program and the Centre for Character and Virtues at Birmingham University, which are looking into what makes people feel that they’re living a good life, a flourishing life. And again and again, a sense of purpose or meaning crops up. There’s certainly no guarantee that studying philosophy will enable you to say “Aha! This is the meaning of life.” But simply asking the questions and reflecting on them and having discussions about them can help give you a sense that your life has some purpose and meaning, some narrative structure. Even feeling that you are working towards trying to find out whether there is purpose or meaning can be fruitful.

To sum up, philosophy is not necessary or sufficient for living a good life, but it can certainly be a really helpful resource, and it can be one of the constituents of a good life, precisely because it helps us actualise not just our intellectual but also our imaginative and affective faculties, which both Plato and Aristotle and other proponents of an ethics of flourishing have said are vital for us to fulfil, to get a sense of a rich, full, ongoing human life, one that’s always in development. I said that it provides a solid frame, but that the picture within the frame can change. And the picture doesn’t just change across communities through time and place, it can change in our own lives.

Music gave me enormous joy when I was 20, and it still gives me deep joy, but my musical tastes have changed a bit – I listen to a lot more Beethoven and Bach now, though I still love Dylan and the Stones. Living a good life is an ongoing project, and I want it to start with unexamined philosophy in primary schools, but I also want resources like New Philosopher to help people to continue that ongoing project. It can be part of living a good life in itself, but it can also help give you the critical and reflective skills, and the stimulus to imagination and creativity and empathy, which can all foster a good life.

From the Flourishing edition, available to purchase from our online store.