Please answer True or False:

1. During World War I, the Germans ran a factory to boil down the battlefield corpses of their own soldiers, extracting the fat for use in household and military products.

2. When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, Iraqi soldiers callously removed 312 babies from hospital incubators, leaving them to die on the cold floors.

3. In 2001, passengers on the asylum seeker boat designated SIEV (for “Suspected Illegal Entry Vessel”) 4 threatened to throw their own children overboard during exchanges with Australian authorities. In some versions of the story, children were actually thrown into the sea, as shown in photographs released to the public.

I hope you answered False throughout. There was no corpse-rendering factory. No children were thrown overboard. The evidence from Kuwait is flimsy: see Randal Marlin’s detailed discussion in his Propaganda and the Ethics of Persuasion (2002). In fact, all these tales of horror have been thoroughly debunked. They were, nonetheless, widely believed at the relevant times. They evoked powerful emotions, reinforcing popular support for policies, governments, and even wars. Enormous decisions, and often the fates of leaders and nations, can turn on the credence given to such propaganda pieces.

The word propaganda originally referred to the work of propaganda fide — missionary activity or propagation of the faith — a long-time project of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1622, the task was assigned to a new body within the Church, the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide), which has since been renamed the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. The word originally had no pejorative meaning — if you were getting your message out, you were producing propaganda — but it acquired nasty overtones during the early decades of the twentieth century, as the dishonesty of much secular wartime propaganda came to light.

In 1928, the famed public relations guru Edward Bernays published a short book, Propaganda, in which he resisted the growing tendency for the word to become pejorative. For Bernays, wise propagandists were needed to guide the vast number of people in modern societies who were ill-equipped to think and plan for themselves. The point of advertising and public relations, of “propaganda”, was not to deceive but to make new products and ideas more salient, to draw attention to them and overcome non-rational aversions.

Some contemporary theorists still use the word propaganda in a relatively neutral way, but this cause was lost even by 1928. Today, the word usually signifies one-sided, emotionally manipulative, and (most especially) dishonest efforts to influence public opinion. Though propaganda materials are commonly aimed at large populations, the relevant “public” might be a smaller one. Thus, we can speak of propaganda intended to influence opinion in an industry sector or within a relatively small population such as the student body of a university or the membership of a club. The pejorative label propaganda may be justified even if the audience is fairly small, as long as its members are subjected to dishonest, emotive, one-sided materials aimed at influencing their thoughts.

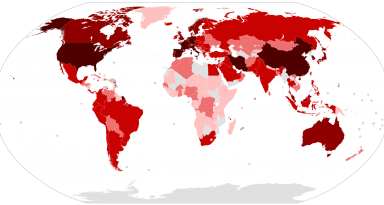

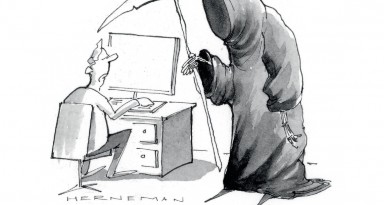

All too often, propaganda succeeds. The mass media have a dismal record of spreading politically convenient fabrications, adding immensely to their credibility and their penetration of public awareness. As Noam Chomsky has been documenting for decades now, even supposedly “liberal” news outlets often act as willing purveyors of the latest war propaganda from the US government of the day. Although the popular press sometimes acts as a critic of official narratives and excesses of public power, it is distinctly unreliable in these roles. When they do oppose Western governments, the news media usually act in the interests of other powerful organizations, such as large business corporations. Marlin and others have observed that we live in an age of propaganda.

Earlier, I highlighted propaganda efforts for what might be seen as right-wing causes, such as wars and xenophobic refugee policies. But governments of all political shades have resorted to dishonest campaigns aimed at mass persuasion, as have many other groups and individuals broadly linked with the Left. We are bombarded every day with one-sided, dishonest, emotionally manipulative messages coming from highly varied sources.

Unfortunately, it can be difficult to draw the line between outright propaganda and less harmful or even beneficial messages. Commercial advertising may fall short of blatant dishonesty — if no lies are actually told — while insinuating dubious claims about the products being hawked to us. Whether or not we call it propaganda, advertising is an ever-present source of distorted information. Far beyond any of this, parents, teachers, religious organizations, and the popular culture as a whole converge to endorse many values and ideas. Some may be innocuous, or even of merit, but others are more damaging, such as outdated (yet persisting) ideas about the roles of the sexes. We socialize children into many assumptions that may seem obviously false and harmful to later generations.

Where is our freedom of thought in an age of propaganda? To be fair, all cultures socialize children into the local mores and worldview. At least ours officially permits diversity: many understandings are on offer as to how the universe works and what might count as a good life. Politically, we have considerable freedom of thought and speech. Nonetheless, we can do better. The negative freedom to hold and express opinions loses much of its meaning if our thoughts are formed in an environment saturated with emotionally charged falsehoods and misdirections. Worse, we all grow up in that environment; we are shaped by it long before we have the intellectual capacity to question it.

The internet might once have seemed a tool for resistance, but it does not bring much improvement. True, it offers alternative sources of information, outside of the mainstream media coverage of news and current affairs. But propagandists can take residence on the internet as well as anywhere else, frequently with their own popular platforms. Online propaganda interacts with another problem that manifests as various kinds of hyperskepticism, ultra-cynicism, and conspiracy theorizing.

Think of climate change denialists, September 11 truthers, and Moon hoax aficionados. Such people find each other on the internet, creating online echo chambers. Once again, this is permitted by our laws: generally speaking, people in liberal democracies are allowed to believe weird things without being punished by the government. And to be fair, the denialists and truthers might seem a bit less crazy when we realize how often we really are lied to, including by governments and respected news services. Someone who doubted World War I anti-German propaganda might have seemed like a crackpot at the time, but there really was a massive conspiracy to deceive and inflame the ordinary people of the UK, USA, and other nations. Again, consider those Kuwaiti babies supposedly torn from their incubators (an atrocity narrative brought to us by the large PR firm Hill and Knowlton).

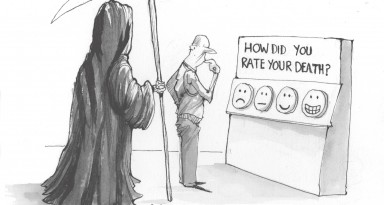

In an age of propaganda, even true and beneficial messages often encounter public cynicism. Part of the problem is that it’s widely known that we live in a propaganda-soaked culture. How can non-experts be confident which sources can be trusted, and why, and which cannot? If trust breaks down, where do we even start in forming our opinions rationally? Some aspects of this dilemma may be amenable to political solutions, but they will not be simple when governments themselves can be so shady. Stronger freedom of information laws might help with that, but they only go so far when the mass media are politically compliant.

What about our own lives? What more can we be doing? Let’s break the problem down. How do we avoid being fooled by propagandists? How do we avoid rewarding propagandists? How do we identify those people who are, in fact, not propagandists and really do deserve our trust? And very importantly, how can we avoid becoming propagandists ourselves when we venture into public debate?

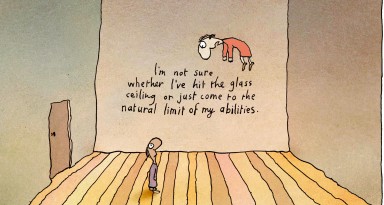

The resolution not to be a propagandist involves difficult commitments: a commitment to represent opposing positions fairly; a commitment to look for the strengths as well as the weaknesses in positions that we dislike, and to accept facts that may be surprising and inconvenient; a commitment not to engage in weakly justified character attacks, or in attempts to browbeat, bully, or demonize opponents into submission; and doubtless much more in the way of openness to the truth. This looks like a pretty tough exercise in self-discipline, so how do we go about it, and how do we teach it to the next generation of citizens?

Such self-discipline is a central, if sometimes neglected, component of modern philosophical practice. A glib solution to the problem that confronts us might be a rallying cry for “More philosophy!” Would that it were so simple: by all means, let’s have more philosophy in schools, universities, and our everyday lives, but we face a problem that is urgent, difficult, and many headed. Identifying it is a start, but where do we go from there? I see no easy solution, but we definitely need to talk.

This needs a better, louder conversation.