To see a person taking in the wonders of the sky is a rare sight when all but a few are staring at their smartphone. What is our preoccupation with gadgets?

Andy Clark and David Chalmers put forward The Extended Mind thesis in the late-1990s, back in the days when smartphones didn’t exist. The central tenet of the thesis is that our minds, thoughts and memory are not confined to our head, but can be extended to the tools and instruments around us.

Smartphones can store phone numbers, addresses, personal photos, videos, ideas and recordings. Navigation systems tell us where we are, and where other things are in relation to us, like banks and shops. These gadgets can act as an extension, or sometimes replacement, of our memory. But should we go so far as saying that these devices are a part of our mind?

“I think the real attraction of the extended mind story is that the activity upon which mindfulness depends is much more spread out than we thought,” says Clark. “Maybe our ongoing use of things like [smartphones] and other sorts of external structures is really part of creating a web of activity, where mind is what happens when that web happens.”

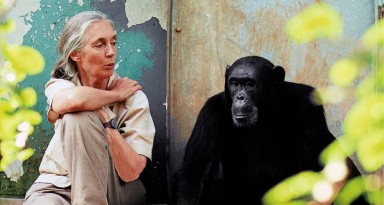

Chalmers reminds us that we have always relied on external things or others to get by in the world. He uses the example of the “socially extended mind” where one person in a couple acts as the other’s memory or when couples finish each other’s sentences. He loosely compares it to people who have extended bodies via prosthetic limbs, or when a blind person uses a cane as an aide for sight. He says gadgets have taken over all sorts of functions of the brain. How many of us remember phone numbers any longer?

Promoters of smartphone applications will keenly point out that their application will “extend your mind”. But before we get too excited, a quick scan reveals that most smartphone applications are hardly mind-enhancing. Take, for example, the paranormal metre application that tells you if a ghost is standing in front of you, or worse, looming right behind you. Or the voicechanger application that allows you to choose twenty custom voices, including “scary” ones.

Indeed, most applications are sold as mere distraction, a foil over life itself. Isn’t this simply a form of extended mindlessness?

For Chalmers, it doesn’t matter if information is stored inside your brain or out there in the world. If it is accessible to you and driving your mental states then it counts as your mind. Inside is the same as outside as long as they are driving the processes, driving the action. There is no barrier around the skull.

Chalmers and Clark present a thought experiment to illustrate the environment’s role in connection to the mind. Fictitious characters Otto and Inga are both travelling to a museum simultaneously, but Otto has Alzheimer’s and has written the directions down in a notebook. Inga is able to recall the directions internally within her memory. She thinks for a moment and recalls that the museum is on 53rd street, so she walks to 53rd street and goes into the museum. In this sense, Inga believes that the museum is on 53rd street and the belief was effectively sitting in her memory somewhere waiting to be accessed.

Otto, on the other hand, relies on the environment to structure his life. When he learns new information he writes it down in his notebook, and when he needs some old information, he looks it up. For Otto, his notebook plays the role usually played by biological memory. When he hears about the exhibition at the museum, he consults his notebook, and walks to 53rd street.

Chalmers and Clark argue that the notebook plays the same role for Otto that memory plays for Inga.

Clark uses the Memory Glasses experiment, a paper written by Richard W. DeVaul at MIT in 2004, as an example of the extended mind in action. The glasses, called wearable computing, were designed for people with Alzheimer’s or visual form agnosia (where people can’t recognise objects in front of them). “The glasses have a little camera that’s taking input from the surroundings,” says Clark. “In the case of someone with mild Alzheimer’s, the system that they’re wearing ‘knows stuff ’, if you like. As it recognises a face, it will give you a very quick flash of information – that’s your wife, uncle, dog. Interestingly, that information can be flashed so quickly that you don’t experience it, but nonetheless it helps these patients to do better.”

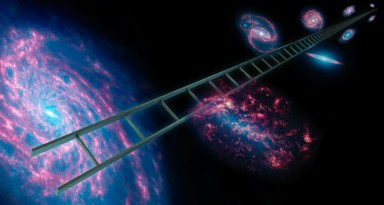

British author Charles Stross’s novel Accelerando offers another illustration of the extended mind, according to Chalmers. Interestingly, accelerando, or “speeding up” in the novel refers to the accelerating rate at which humanity is heading towards technological singularity, regarded as a theoretical moment in time when artificial intelligence David Chalmers is Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and director of the Centre for Consciousness at Australian National University. He is also Professor of Philosophy and co-director of the Center for Mind, Brain, and Consciousness at New York University. Chalmers is best known for his work on consciousness, but is also interested in metaphysics and epistemology, and the foundations of cognitive science. radically alters human civilisation and even perhaps human nature itself. Artificial intelligence, human biological enhancement or brain-computer interfaces are the type of developments that may push humanity to singularity, the theory suggests. In Accelerando most of humanity is wiped out, and capitalism “eats everything”.

“In Accelerando people wear glasses that provide all kinds of information to the wearer,” says Chalmers. “People become totally reliant on them, so when this one guy’s glasses are stolen, he becomes a gibbering wreck in the same way one would if a part of their frontal cortex was removed.”

Chalmers mentions that glasses like these have already been released onto the market; applications can be built into the glasses allowing users to be essentially hooked up, or in the loop, at all times. “So maybe we’re moving into the era where this thesis becomes truer for all of us in everyday life,” he says.

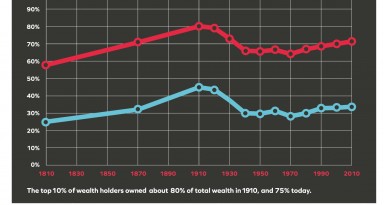

During his May 2011 “Extended Mind” talk in Sydney, Chalmers discussed our increasing reliance on technology, noting that knowledge is power. “It leads to a potential democratisation of the powers of the mind,” he says. “As technology becomes cheaper and available to more, it is going to spread. Phones are spreading, [search engines] are spreading. With time it becomes available to everyone. It is a trend and we are at the very early stages of turning us into superheroes of the mind. And technology is gradually giving us these superpowers, turning us into cognitive super geniuses if you like. And it’s going to go more this way in the future.”

If we were to take a step back we could argue that the watch, or clock, was one of the first gadgets that stored information on our behalf. Before the clock, humans relied on the sun to discern time, and this ability extended to other mind functions such as our internal compass. We used the positioning of the sun or the stars at night to navigate our way around the planet – we’d instinctively know north and south, east and west.

Today, could the average person on the street point to the east? Throw Mr Average into the desert and he is likely to do nothing but stumble about in circles.

The question is, as we download more of our mental functions onto our gadgets, what do we lose in the mix?

The extended mind thesis had its critics in the 1990s and the heated debate continues today. When the article was first published in 1998, Chalmers says: “I saw the attractions of the thesis but had some reservations.

“We had this footnote saying ‘authors are listed in order of the degree of their belief in the central thesis’. Andy was very confident, I was on the fence. It’s probably still true that I go back and forth on it a bit more than Andy. One thing that has made me much more confident over the years has been looking at all the objections that people have come up with. I have to say, they’re really not that strong. You go through the best of them and the most well known ones, and they all strike me as quite easy to requite. If that’s the best they can come up with to reject the thesis, it’s starting to look quite good.”

Clark agrees. “I haven’t actually seen anything that strikes me as a convincing objection yet. In fact, I think, most of the things that are put forward as objections, we more or less anticipated in the paper. There are tricky cases, you know. One of the things that might give you pause is, for example, the role of perception in the cases of the extended mind. It always seems like in all of these cases there’s something perceptual going on.”

Chalmers continues: “To say it’s got to be bound by the skin or the skull, it seems unprincipled to me. If you want to look for something principled, argue that perception and action are the boundaries of the mind. When Otto reads the notebook he’s doing it via perception, and the mind is what happens

on the other side.”

In any event, the extended mind theory has leaked into other disciplines. Evelyn Tribble at University of Otago and John Sutton at Macquarie University are working on a cognitive history built on the extended mind theory.

The theme under investigation is one that has stumped historians for centuries: how did actors in Shakespeare’s day remember their lines? Actors performed anywhere from 60 to 70 plays a year – several plays each week – with few repeat performances. Historians have often thought that a single prompter, with the whole text as a kind of blueprint in their mind, continually fed actors their lines. But Tribble disagrees.

She applied the extended mind thesis to explain how actors coped under these extraordinary demands. Tribble argues that the system, the architecture, or the physical layout of the theatre, remembered the information for them.

Only certain scenes happened on balconies, for example, or at particular entrances and exits. An actor would remember the line to say while cradling a baby under a tree, or slicing the arm off an opponent; the lines related to the particular array of characters around, the type of activity, the physical layout, and the gestures. Lines were not remembered in isolation.

The theory suggests that we humans learn, and our mind operates, from the outside in, from our parents and from society around us. It implies that our mind is altered by the social system or physical environment that we find ourselves in. Alter the way we remember, think and make decisions via gadgets and what mind do you get?

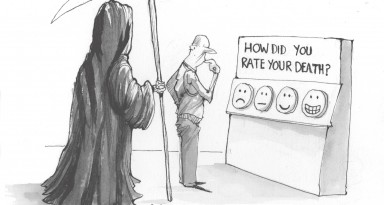

At the closure of his Sydney speech Chalmers points out the ethical issues we face: “The question is: will we use these powers for good or for evil? That is the gift of the extended mind and the challenge it presents as we move into our extended future.”

Ubiquitous computing is a concept where objects, both constructed and natural within everyday life, have embedded technology that communicate and connect to us wherever we are. We no longer plug ourselves in; the technology is everywhere.

No one doubts that we can connect more than we did before. But we do need to ask ourselves: why? Why are we downloading, uploading, comparing hotels, playing Tetris? What’s the point of all this? Why?

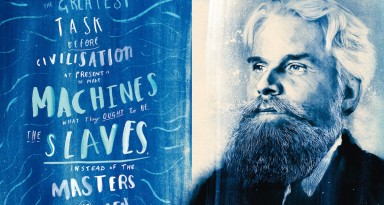

If we lined up an educated student 100 years ago with an educated student today, who would be regarded as the superhero of the mind? Would we marvel at the photo-sharing abilities of today’s student? Would we applaud the number of applications they had downloaded onto their smartphone?

When you bake in the sun of ubiquitous computing, have a think about whose rays you are exposed to. Are you extending your own mind, or simply giving over control?

Like Shakespearean actors, our memories cling to the physical layout of our world, or to novel and unusual events. We can easily recall a sun-filled day spent in Greece, the day we moved house, or broke a leg.

Moments spent online, in contrast, are difficult to remember regardless of how entertaining or shocking they were at the time. In fact, can you even recall a single significant moment spent online?

When we stare into our smartphone or computer screen, the physical world is removed, and our minds - with nothing to cling to - struggle to remember much at all. And as we ratchet up more and more hours online, the lost moments begin to stack up too.

Antonia Case is the literary editor of New Philosopher magazine. The interview with David Chalmers and Andy Clark was conducted by Signe Cane at the 9th International Symposium of Logic, Communication and Cognition hosted by the University of Latvia.