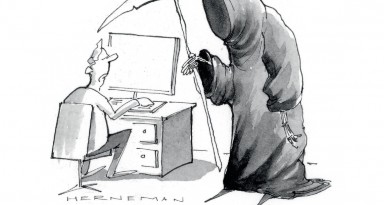

The path laid out for Australian-born Tim Cope was to go to university, get a job, a career, a house and a mortgage; he took the first step by getting into law. But sitting in a law library on his first day at university “felt like death,” says Cope. “And when I went to my first lecture, my heart sank.”

The lecturer, high on the podium, announced: “Congratulations for choosing law. The foundations of law mark the beginning of civilisation.”

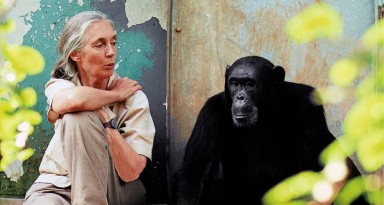

Months later, Cope was standing alone on the Eurasian steppe, a 10,000 km belt of grasslands stretching from Mongolia to Hungary with the sun coppering his face. An image of nomads galloping over the horizon from what felt like nowhere haunted and inspired him. “I never imagined that people still lived like that in our world,” he says.

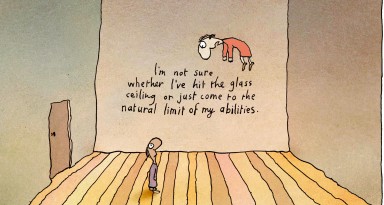

As he looked out across the steppe as the last shadows ran across the land, Cope felt that the future was totally open, a “scary, but really good feeling.” Was this what Kierkegaard was referring to when he wrote about the “dizziness of freedom”, the anxiety or despair we suffer when we have absolute freedom to choose how we live our lives?

For Cope, nomadic life offered a glimpse into the nature of people before so-called civil society. Are people naturally savage, brutish and self-serving? Do we need a government or central authority to make us behave?

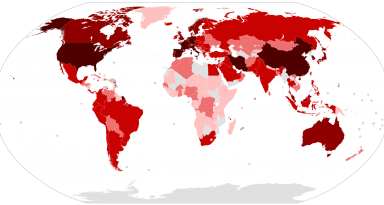

Eurasian nomads live outside the boundaries of civil society, obeying no law except the laws of nature. Nomads move three to four times a year in search of pasture to feed their animals, herds of camels, horses, sheep and yaks, moving at their own pace, sometimes using old Soviet-era trucks to carry their scant belongings. Private property does not exist. There are no fences, roads or super-highways. Children don’t go to school, wear uniforms or learn national anthems.

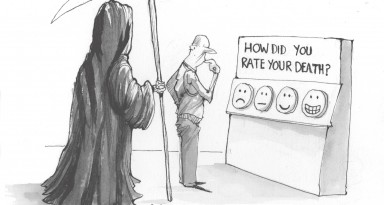

In Leviathan, English philosopher Thomas Hobbes warned that without civilisation to place restrictions on man’s self-interest, man would resort to a “warre of every man against every man.” People would live in a state of “continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” He called this condition the “state of nature” and in this state every person will do whatever necessary to preserve his or her own life. To avoid this state of nature, argues Hobbes, people must accede to a social contract - beneath a sovereign authority - ceding some rights for the sake of protection.

With his three horses, Cope left the old Mongolian capital of Karakorum, headed for Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine and eventually onto the Danube River in Hungary. But five days into the journey, he woke at 2am to the sound of galloping hooves fading into the inky sky. He rushed barefoot into the darkness to learn that his horses had been stolen. The cold harsh wind of the steppe – its gaping emptiness – offered no protection.

The following day at dawn, Cope retraced his steps. On the horizon, he spotted a herd of horses moving swiftly, a single horseman in charge. On approach, Cope recognised his two horses among the pack. “These two horses came to me this morning,” the horseman said grinning. “You must have tied them badly.”

The horseman returned the horses without compensation, but insisted that Cope understand an important unwritten rule of the steppe. “A man on the steppe with no friends is as narrow as a finger,” the horseman said. “A man with friends is as wide as the steppe.” Before setting up camp in the open overnight, approach the nearest yurt, even if it’s on the distant horizon, the horseman stressed. A nearby family will offer protection, hospitality and help.

For the following three years, over 90 nomadic families gave food, shelter and companionship to Cope, saving him from the extremes of the climate – taking him in from the icy storms that rolled unpredictably across the steppe. They offered him kumis and freshly boiled mutton, reshod his horses and entertained him with the dombra, a two-stringed Kazakh instrument. Hobbes’s selfish and savage “natural man” he did not find, not until much later.

Long days in the saddle offered many moments of contemplation. Cope reflected on how little he thought about time, how slowly his needs moved to predominantly concerning himself with the needs of his horses. “I started to look differently at the world. Where is the good grass? Where is the good shelter? What does the horse need?” He also thought about his parents and how they were feeling with him so far away.

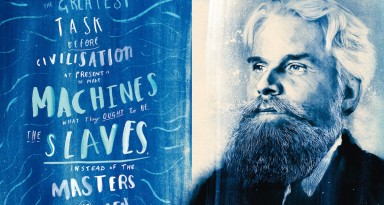

French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau takes a radically different view on human nature to Hobbes. He says man is born free, innocent, happy and fundamentally good. “Natural man,” says Rousseau, is endowed with attributes of compassion and empathy.

The selfish, savage and competitive nature described by Hobbes is, for Rousseau, a depiction of not “natural man” but of “civilised man”. Rousseau claims that society corrupts, separating humankind from nature. “Man is born free, yet everywhere he is in chains,” he wrote in his most influential work, The Social Contract.

When Cope first cast his eyes on nomads galloping over the horizon, people living in Hobbes’s hypothetical “state of nature”, he says it was like a “childhood dream of freedom...it was like a fairy tale.” A far cry from growing up in country Gippsland, where a thousand fences obscured his path to the hills.

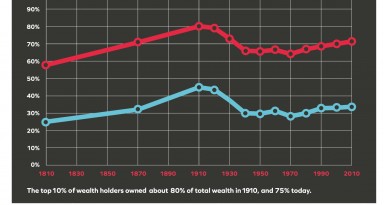

For Rousseau, once land is enclosed for an individual’s purpose, a system of laws is needed to protect the land from others. These laws, said Rousseau, are unjust and selfish, rules that are inflicted on the poor by the rich. As the natural state moves to a civilised state, Rousseau sees human virtue turning to vice, and innocence and freedom to injustice and slavery.

In nomadic society, in contrast, everything is communal, the earth just one circular tent. At night, nomads climbed unannounced into Cope’s tent for a chat, a cigarette and some fermented milk or yoghurt. Nomads take in strangers without asking questions, housing and feeding them for days, simply because that’s what’s done. And after three days, the tradition says that you can ask the stranger what his business is and where he is going. “Nomads are not poor,” stresses Cope. “If they need food they can slaughter some animals. If they need money, they can sell some animals and get some cash.”

But once man is separated from his environment and animals, Rousseau points out that our innate virtue turns to vice, and the nasty, brutish side of human nature takes reign. Our happiness turns to misery.

Cope’s dog, Tigon, was stolen in a gold mining village, and for seven days Cope desperately searched the streets fearing the worst. Miners were rumoured to steal dogs to eat and Cope’s dealings with them did little to dispel this notion.

Cut off from agriculture, miners fight each other to survive; without animals and land, the men live off low wages and contraband dealings – taking gold illegally and selling it on the black market. “It was shocking to go from this romantic way of life where people were gentle, tolerant and generous to a society where it was just survival,” notes Cope. “In the mining towns there was no generosity of spirit and the walls were up; there was a lot more greed and people were stepping on each other. I saw the less delightful side of human nature.”

After finding his dog unscathed, Cope set sail with his horses on a ferry across the 3km Kerch Straight, and arrived in the Ukraine, journeying across the Crimean steppe, battling thick forest and cavernous gullies. One night he was invited to put his horses in a barn, but his horses were petrified, and repeatedly tried to barge through the door. The farmer said to Cope: “Your poor horses; it has been so long since they were in the stables that they’ve forgotten what it is like.” Cope replied: “The problem is that they’ve never been in stables.”

Looking back, Cope muses: “It just shows how conditioned people become in Europe and the West. People believe that horses are born in stables, when in actual fact, putting a horse in a stable, giving it shelter and warmth from the cold and the rain and giving it hay - while people believe this is treating the animal well - for the natural horse there couldn’t be anything worse.

“The horse needs freedom; it needs to roam; it needs to graze; it eats 24 hours of the day; it is a herd animal; it hates being separated; it needs freedom; it is innately nomadic and it evolved that way. To them the stable is absolute misery.

“And if you think about that in human terms, of a human locked up in four walls in an apartment in the city. That is a prison as well.”

On a Sunday morning, a week after arriving back in Australia, a loud banging erupted from Cope’s front door. It was a neighbour from down the road. Cope’s dog, Tigon, had set foot on his property and the neighbour, red in the face with fury, was threatening to call the police.

He was back in civilisation once more.