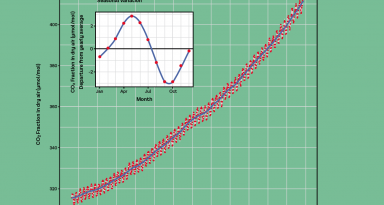

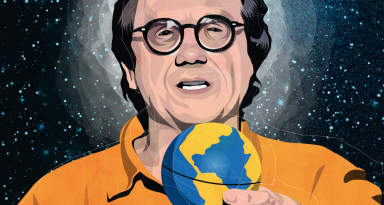

“The decade that just ended is clearly the warmest decade on record. Every decade since the 1960s clearly has been warmer than the one before.”

Gavin Schmidt, NASA GISS Director

A few years ago, the American novelist Ben Dolnick described an epiphany he underwent after he began regularly taking ice-cold showers. He wasn’t expecting to like the experience – and, sure enough, he didn’t. But a more profound alteration took place: he found himself relating differently to the very notion of liking and disliking things. “At almost every moment of the day,” Dolnick wrote in The New York Times, “I am accompanied by a pair of petulant, melodramatic children in my mind’s back seat. These children, Liking and Disliking, exert a distressing degree of control over just about everything I do.” Yet his shower experiment proved that when he ignored the screaming objections, Disliking soon piped down, and Dolnick could relax as the water hit his body: “Those urgent pleas, those desperate warnings, turned out to have been a passing squall.” He was cold, but he was fine. And he’d confirmed the truth of an insight with roots in ancient philosophy: that to be overly influenced by one’s likes and dislikes is a kind of psychological enslavement. Dolnick’s preferences now exerted a looser grip on his behaviour. During the rest of the day, he felt less constrained by the need to do what he liked and avoid what he disliked – which left him freer to focus on doing what mattered instead.

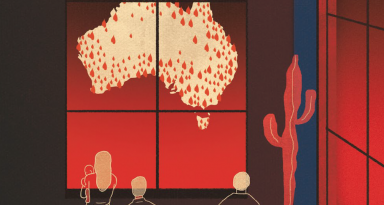

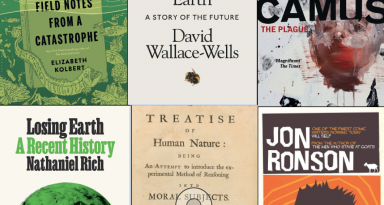

Perhaps it seems perverse to draw wisdom about the climate from Dolnick’s exertions in the bathroom (other than the fact that freezing showers are presumably a good way to conserve water, since there’s little temptation to linger). But I think we can. The argument goes like this: when it comes to engaging with the present emergency, we face an inadequate menu of attitudes. There’s denial, which plainly won’t do; and despair, which leads to passivity. There’s also dread, the attempt to scare ourselves and our leaders into a better response – but I’m inclined to agree with the environmental technologist Matt Frost that “it is time to acknowledge that catastrophism has failed to bring about [a] global political breakthrough… we have reached diminishing returns on dread.” Finally, there’s the seemingly preferable option of hope, in a social, political or technological transformation that might pull us back from the brink. But like all the others, hope comes with a catch: it yokes the possibility of action to the likes and dislikes of the person doing the acting.

The denialist, after all, pretends that nothing’s wrong precisely in order not to have to confront a scenario he dislikes, while the despairer is unable to act because he’s convinced that a scenario he dislikes is unavoidable, or has already arrived. Dread, on the other hand, is the attempt to motivate people by threatening them with the prospect that a scenario they’d deeply dislike might come to pass, while hope depends on maintaining the belief that such an outcome can be avoided. Obviously, “dislike” is putting things far too mildly, when we’re talking of ecological catastrophe. But thinking in such terms raises the intriguing possibility that, like Dolnick in the shower, we might be able to adopt a different attitude – one in which facing the reality of our situation, and engaging vigorously with it, would be less entangled with our preferences, less dependent on whether or not things are unfolding as we’d like.

The denialist, after all, pretends that nothing’s wrong precisely in order not to have to confront a scenario he dislikes, while the despairer is unable to act because he’s convinced that a scenario he dislikes is unavoidable, or has already arrived. Dread, on the other hand, is the attempt to motivate people by threatening them with the prospect that a scenario they’d deeply dislike might come to pass, while hope depends on maintaining the belief that such an outcome can be avoided. Obviously, “dislike” is putting things far too mildly, when we’re talking of ecological catastrophe. But thinking in such terms raises the intriguing possibility that, like Dolnick in the shower, we might be able to adopt a different attitude – one in which facing the reality of our situation, and engaging vigorously with it, would be less entangled with our preferences, less dependent on whether or not things are unfolding as we’d like.

As a label for such a stance, we could borrow the term “apocaloptimism”, defined as the attitude of someone “who knows it’s all going to shit, but still thinks it will turn out OK.” This is an oxymoron, of course. But it’s a potentially useful one, in that it short-circuits the whole question of whether or not we like what’s happening, instead redirecting attention back to what’s happening, and how we’re called upon to respond. The apocaloptimist might take rueful comfort in the observation of the psychotherapist Bruce Tift that the glass is never really “half full” or “half empty”. On the contrary, it’s always entirely full, of some combination of water and air – just not necessarily the combination we happen to prefer.

And this realisation is liberating. The apocaloptimist can volunteer to help clean up a polluted canal, or rebuild homes damaged by a natural disaster, without first demanding to know whether she’s “making any difference”, in an ultimate or planet-wide sense, but simply because it needs doing. She need not pick a side in disputes about tactics – between, say, the civil disobedience of Extinction Rebellion, versus research into bioengineering solutions – because she can follow where her skills and energies lead her, freed from the need to feel confident that she’s chosen the best path, because she knows that’s unknowable. The environmental activist Derrick Jensen vividly captures the bracing sense of possibility that can result from moving past this internal demand for hope: “One of the good things about everything being so fucked up,” he has written, “is that no matter where you look there is good work to be done.”

There’s a specifically temporal shift to be made here, too – a change of perspective in which we surrender the expectation that we might get to find out, within the span of our own lifetimes, whether our efforts were worth it, or whether humanity will make it. The idea that such rapid feedback ought to be the norm is probably a mindset peculiar to our technologically accelerated age. Whenever I pass York Minster, the vast cathedral in my northern English hometown that took around 250 years to build, I’m reminded that most of the stonemasons who worked on it couldn’t reasonably have expected to see it completed. Yet I doubt it would have occurred to them that their work lacked meaning as a consequence. And while it surely helped that they felt they were labouring for the glory of God, we secular types could stand to learn a lesson: that our care for the planet and its inhabitants need not be dependent on any thought of seeing our efforts through to completion.

But apocaloptimism shouldn’t be mistaken for a kind of saintly, hair-shirt selflessness, requiring you to ignore your own desires altogether. That’s probably impossible, and in any case I’m not sure it’s desirable: I care about the climate at least in part because I care, in a selfishly particular way, about the future of my young son, not just the future of humanity in general. Rather than jettisoning his likes and dislikes altogether, the apocaloptimist merely refuses to let them tyrannise him quite so much. Whereupon he discovers that, if facing up to reality doesn’t exactly make for a happier experience of being human, it certainly makes for a realer one. The paradox is that loosening the grip of one’s preferences, it turns out, is a preferable way to live.

< News from nowhere | The Dancer >