Interviewee: James Thornton

Interviewer: Zan Boag

ClientEarth is an environmental law charity that you founded 12 years ago, now with offices in London, Brussels, Warsaw, Berlin, and Beijing. On the website, it states that you “use the law to hold governments and other companies to account over climate change, nature loss, and pollution”. What prompted you to start Client Earth and how do you hold governments and companies to account?

We’re set up as a group of international lawyers, formed as a charity, and in place of a traditional client we have the Earth and everyone who lives on it – so you, and all your readers are our clients, and we try to act on behalf of everyone who lives on it. I had done a lot of work in the United States in the interest of the public and to save the environment which was started around by a couple of different organisations in the US. I started doing that work with one of those in 1979 and set up an office in Los Angeles to do such work. Then I became essentially an exile from the US due to the fact that my partner, now husband, wasn’t allowed to stay in the United States. So, I left the United States – the human rights lawyers were better in Europe than in the United States at that point. I looked around and I saw that in the European setting, the environmental groups weren’t using law in a strategic way, in a way that I had been doing it in the US. There wasn’t any non-profit environmental law firm working at the European level, so there seemed to be a wonderful opportunity to contribute to the whole European environmental community. And that’s the way it started. And the basis of it, and what keeps me going, is my own Zen practice because it’s the why do I care each day. You’ll be familiar with the Bodhisattva vow, which is to save all sentient beings, and I take that in my work in a very literal-minded way. My work as an environmental lawyer and the head of a charity is indeed to try and save all sentient beings.

It’s a pretty good ‘why’ that you have there.

[Laughs] It’s a good brief. Given that climate change is real and very pressing, if your client is the Earth and to be focused on it in this way gives you the energy you need to keep doing the work.

And energy is what’s required – it’s such a ferocious battle that needs to be fought. I imagine that you’re working on a number of interesting cases. Could you run through one of the cases you’re working on at the moment that looks promising from your point of view?

Let me sketch out the litigation that we’re doing in the European context. It has about 50 cases going on against coal in one way or another, and there are also about 50 cases on air quality, to get diesel out of the market and drive the transport fleet towards being electrified. One interesting case, which has just been completed so I know that it’s a success, was against a coal-fired power station with a very novel approach. So, we’ve prevented the building of 38 coal-fired power stations in Europe since we started 12 years ago. One of our goals is to ensure that there are no new coal-fired power stations built in Europe. And we’ve succeeded – there haven’t been, we’ve stopped all of the new ones. But in Poland, the government was very keen on building what it was calling “the last new coal-fired power station” in Poland. Which was a sort of back-handed compliment to us. So, we said, OK, we’re going to take a novel approach. We’d been using environmental law but this time we said, let’s step aside and use a purely business approach, a purely company law approach. We commissioned an economic study by an independent company saying that this new coal-fired power station was going to be uneconomic because the cost of renewable energy was falling very rapidly and it would beat, in the market, this new coal-fired power station. So that it was simply a bad investment. So, we said “great”, we bought shares in the company, went to the meeting where decision had to be made, and we voted against, we voted our 30 euros worth of shares, and it helped that we brought 40 per cent of the shareholders with us. But the government had a slight majority, and it went ahead. We personally sued the officers and directors of the company and we alleged that they had violated their standard corporate duty of care to their shareholders by knowingly making a bad investment in coal. And what happened, and this is Poland, quite conservative in many ways, the business newspaper, which years earlier had denounced us, ran a series of articles about this case and it never even mentioned that we were environmentalists in any way. Which was fascinating. What they said was that investors question future of coal. And that’s how it was discussed – it was discussed very seriously as a purely business thing. And then, the best news is that we hired the best securities litigator in Poland; we won the case against the officers and directors. And here’s the punchline: the next day, the stock price went up almost four per cent. Isn’t that great? The market was with us. That was a beautiful moment. In terms of litigation, and nobody knows it yet, it is what China is doing. So, I started working in China in 2014 to advise the Chinese Supreme Court in writing a law to allow citizens and prosecutors to bring cases. Citizens against companies; prosecutors against the government. And then they invited us to start training judges to decide environmental cases – we’ve trained at least 1,000 judges by now. And they set up environmental courts, quite unlike anything in most of the world. We trained the judges, and the prosecutors came to us and said, “In that law that you helped write, we got the right to sue the government on behalf of the people for environmental issues if they weren’t doing their job. But we’ve never sued the government – we’ve never had the right to sue the government before. You sue governments all the time and you seem to win. Could you train us to sue the government?” What a remarkable question. So, we did start to train them, bringing in experts from all over the world, and then 2018 was the first full year of their new activities in bringing environmental cases as the federal prosecutors. So, the following January, January 2019, we sat down with them and said, how many cases did you initiate in 2018? And the answer was: 48,000. Extraordinary.

Do you find that you face more barriers trying to change legislation in the UK, or the US, or in European countries?

What’s interesting is that in China there have been no barriers because the government from top to bottom is aligned to make as much progress on the environment as soon as possible. When they invite you to help them do something, it really happens. And they’re really keen to make change. In terms of being global leader on the environment – the United States used to be one – at the moment it’s China, and what they’re doing is very exciting. So, 2018 there were 50,000 cases, almost, 2019, same, around 50,000 cases, and many of those, something like 70 per cent, were actually against governmental entities that weren’t their job of enforcing the law. So, what they’re doing very effectively is to say what is the fastest way we can create the rule of law for the environment in China so that everybody, whether they’re a government official in some province, or a company, knows that they have to comply with the law. And businesspeople in the west tell me that they see the changes already, after only a couple of years. The attitude is very much changing, very rapidly. In the west, companies know that they have to comply with whatever the law is – they don’t always, but generally you know that there’s a likelihood that you’re going to get caught and prosecuted, so people tend to comply, but in China that wasn’t the case, but is rapidly becoming the case. In a sense, I love the cases that we bring, but the cases that are most important are the 100,000 that we didn’t bring in China.

You say that in the west, generally companies comply with legislation, however is it an issue that changing legislation is a very difficult thing to do?

Yes. The way I often think about it is that if we enforced all the environmental laws currently existing, would you stop pollution, would you stop plastics turning up in the ocean, would you stop climate change, and the answer at the moment is ‘no’, even if you enforced them all perfectly. And they’re not enforced perfectly. What you really need is environmental law 2.0, and it is difficult to get things through. An example is that the EU is trying to do a pretty good climate change law and we’ll see if the new commission gets it through. But that’s the question: will it get it through? And it is pretty difficult. Companies often threaten to leave and move somewhere else – I’ll move from Belgium to Indonesia if you tighten the law. It more of a threat than a reality because to a large degree companies are able to do lots of damaging things to the environment under the existing law. Here’s a European case involving climate and plastics. The oil and gas industry knows pretty well now that society will have to start using less oil and gas, in the coming decade and further decades. But they have no intention of selling less oil and gas, so their own consultants have publicly described what they call their Plan B. Plan B is to take the oil and gas and use it as feedstock, which is it, for plastics, and yet more plastics, and yet more plastics. If society is smart enough to stop using oil and gas, oil and gas companies are keen to start seeing the production of hugely more plastics. This is a terrible strategy for saving civilisation. The movement in that direction has already started. For example, there’s the biggest plastics manufacturer in Europe, one of them anyway, it’s called Ineos, and they tabled plans for a huge expansion of their plastics facility on the border between Belgium and the Netherlands. Because, here you see, even if you stop all the coal-fired power stations, if you have all these plastics facilities increasing in scale then each of them produces as much emissions as a big coal-fired power station and then they also produce plastics, which is a tragedy in itself.

Is the problem here because of the profit motive that is inherent in the way companies are set up that it must make more profit each year otherwise the heads of the company will be removed. Is the problem here that companies are driven by profit first and foremost and whatever happens, whether it is good or bad for the environment, is irrelevant?

Yes, to the question that whether it is good or bad for the environment is irrelevant, but that’s what the law can change. I think the profit motive, at least for a while, could help us a lot in driving innovation. If we are going to save civilisation then we’ll need to reinvent the way we do everything. We need to reinvent transport, we need to reinvent how we create energy – we need energy systems – we need to reinvent agriculture, and so on. All of these things will take enormous investment and that has to come mostly from the private sector and for those people who are willing to put their life on the line to say build renewable energy systems, rewarding them with profit is fine. I’d say to your very deep question, let’s examine whether we can do without a profit motivation at some point when we’re more mature as a civilisation because we have been wise enough to redesign our energy systems, redesign our transport and so on. The main issue at the moment is that there are many big incumbent industries focused on the wrong activities. They weren’t intentionally set up to do bad things; we discovered it along the way. But the problem is that they have so much power that it is very difficult to dislodge them. Incumbent industries, say, in the energy sector, are still burning coal in Europe. They don’t want to stop burning coal at all, hence us suing them. But who is going to change them? That’s the question. The good news, I should say, is that economics is finally on the side of the environment, and the future of people’s health and all that – renewable energy is now cheaper than coal-generated energy. But you have to make the transition and the transition is a huge change and the incumbent industries are like huge dragons sitting in the middle of the river. They don’t intend to move and governments are unlikely to move them because they’re deeply intertwined with governments, you see that in Australia certainly, and the new industries that want to produce renewable energy in a clean and lovely way, aren’t set up to attack the dragons because they’re smaller. Who’s going to do it? That’s where citizens come in, a Zen monk with a sword attacks dragons and the hope is to clear them out of the way so that the people who want to do the right thing have access to markets, have access to capital, have access to people. If corporations – in their current design, and with their current directions – are producing these results that will be catastrophic, how do you change them? That has to be by changing the rules. It isn’t enough to say that companies will lose their social contract because people will vote with their money and go somewhere else. That’s fine, and it’s a good idea, but it goes much, much deeper than that. You have to change the rules. And there are some rules you can change. For example, you could say, and we will be trying to get this to happen, you could say that all companies listed on the London Stock Exchange, for example, if you’re going to be listed there you need to come up with a business plan that shows that you can become carbon neutral or carbon positive in everything that you do and all the uses of your product by a certain date, just tell us: 2050 or 2040, something like that. And then, that you must actually act on that plan. You have a curve, and you have to reduce your emissions along that curve in a way that will match what the scientists say we have to do, and the law says that you have to hit that curve, you have to reduce, reduce, reduce. And governments are talking about doing that on a national basis, but it doesn’t involve companies at the moment. When the EU is saying that all European countries will reduce their emissions by this amount, they’re looking at 2050 and have come up with a plan to do it, so far nothing is binding companies. If the companies were actually told that they need to do this, then they would in fact do it.

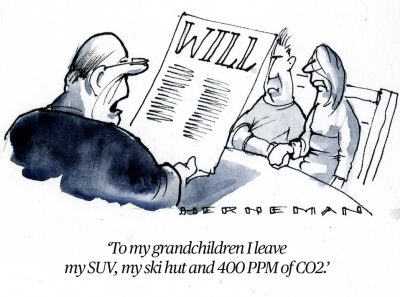

What do think of the way individuals are made to feel bad about their choices? Of course, individuals have a role to play in what they choose to consume, but does putting the onus on individuals, in a way, let companies and governments off the hook?

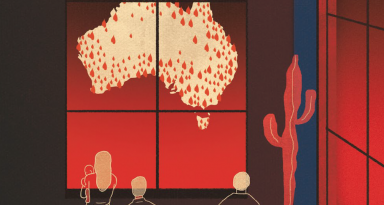

Your question is a very important one. And it’s important for all of us to become aware of these things, and indeed to modify our behaviour. And there are easy things you can do: you can eat a lot less meat, for example, it’s enormously helpful; you can not waste food – I was looking at numbers the other day in Britain that the normal household throws away 25 per cent of its food as waste. That’s easy to change, and those would make significant and important differences, but nowhere near enough. What I think those things are important in doing is, first of all, making some kind of contribution, making people understand that there is something they can do, but real change has to come from governments and companies. Really governments, because companies, as we were just discussing, the companies that need to make changes the most, won’t make them voluntarily – they need to be told what to do. What can people do about that? Well, vote for the people who will do the right thing. The children of the world should get organised and demand change, otherwise politicians will tend to drift along and do whatever they do. And politicians in Australia at the moment, who slightly won the last election, are clearly captive of the coal industry – that needs to change, and people can change that. The people in power in Australia at the moment are unlikely to change their own minds… but it was very close – it was like the Brexit election in the UK. It was a very close election. People who vote, who could vote, need to do so, whether you’re kids or retirees, you need to make sure that politicians understand that you really care about whether they vote one way or the other on these issues. So, there’s a lot that people can do, and it’s very empowering that you can do something, not only at home but also politically. That gets you over the despair, the depression, that is a natural part of understanding the difficulties. Once you understand the difficulties facing civilisation, once you have the information and you’re open to it, a natural response is to feel bad. That’s an intelligent response because the news is not good news. The question is, how to go beyond that and beyond the anger that comes from that and find a positive step to take.

Despite the despair that many do feel and the fact that the crisis is increasing in magnitude, there is a lot of hope in that people are getting together, people are discussing this more – it is on the table for politicians and for companies. Despite the fact people are rallying more around this issue and looking for solutions, I imagine that you get quite a lot of pushback. There must be some individuals and companies that aren’t too pleased about the work you’re doing. What sort of pushback are you getting, and where are you finding the most resistance to the changes you’re trying to implement?

In court, you’re fighting, so there’s resistance there, but if you pick your battles carefully then you win. Those are, in a way, set-piece battles and we generally win cases. In legislatures there is a whole array of forces that you encounter. In Brussels, for example, there are something like 15,000 corporate lobbyists. There are a couple of hundred environmentalists, and we are the only group of lawyers working with the environmentalists. There is a tremendous force on one side, and then you have to make arguments when you’re discussing legislation, reason economics and investment in the future. And to a surprising degree, you can make progress. You might expect that we get a lot of physical threats, and happily we don’t. In Poland, in the beginning, when we started by suing 14 new projects that were coal-fired power stations, then we were in fact shut down by the secret police – our office was shut down by the secret police a couple of times, they went and investigated us and talked to all the other environmentalists that they could find and they kept asking them: “Who do these people actually work for? Are they foreign agents?” And there were threats around that time. But what’s interesting at the moment is that a number of companies are beginning to ask for advice, and that is a shift. So, we set up a team of corporate lawyers, and it’s the only such team in the world, and we’re saying what corporate regulations should look like. For example, the risk of climate change for pension funds. And what has been happening is that we did change the pension fund rules after some years of work lobbying for that, and the pension fund rules require that you take into account the risk of climate change in the stocks and bonds that you buy. That’s good. And then pension funds came to us and said, “What does all this mean?” What started happening is that we were advising them – companies and pension funds, the smart ones, were saying “we see the changes coming… can you give us advice on how we can change quickly so that you don’t come after us.” And I’m very happy to give people lessons on how not to be sued by us because that is really efficient. If they’re smart enough to see the writing on the wall, then we can help them.

Let’s say, you’re installed as ultimate legislative ruler of the Earth – you determine the rule of law, what companies can and can’t do, how individuals can and cannot behave. What are the first laws you’d write for companies? And the first ones for individuals?

Let’s say, you’re installed as ultimate legislative ruler of the Earth – you determine the rule of law, what companies can and can’t do, how individuals can and cannot behave. What are the first laws you’d write for companies? And the first ones for individuals?

First, I’d invite a lot of kids to join me. But seriously, I was talking before about environmental law 2.0 and that’s the next stage, but what you’re asking is what the fundamental shift has to be – and it’s a wonderful question that very few people ask. My deep feeling about this is that you need to, in a serious way, change the rules of the game. If you design the rules of the game in a way that conduct which is deleterious will no longer be on anyone’s screen – it just won’t be an option. And that needs to be in the way we generate energy, so that generating energy from coal just isn’t possible. And instead we generate renewables, we use hydrogen for storage. Australia, for example, could become the world leader if it cancelled coal projects, built a huge amount of renewable and it used a lot of renewable energy to separate the hydrogen from sea water and then sold the hydrogen as ammonia to Asia instead of selling coal. So, if change the rules of the game then that would become more attractive. For energy systems you need to say, “How do you build an ecological civilisation?” so that energy systems are not destructive in any way. For agriculture – how do you build an ecological civilisation so that agriculture not only delivers food that is cleaner and healthier, but that agriculture also sequesters carbon, agriculture helps biodiversity; how do you do that? And you need to do it with industrial policy, you need to rewrite the rules of the game so that nobody can burn coal, so that you use hydrogen to make cement – it would be perfectly clean, and you need to make cement, and that would be a perfectly clean way to do it, but you need to rewrite the rules for industrial policy. Transport: the same. You need to rewrite the rules of economics, the thought systems of economics, so they don’t direct you towards destructive activities, but only towards activities that harmonise with global Earth systems. For law, you need to redesign the legal system so that all these things I’m talking about are captured in the right sort of rules which we can enforce, citizens can enforce – everyone is empowered to do that. If you do all these things, you’ll end up designing an ecological civilisation. It has been a dream of mine for a very long time, and one the remarkable things about going to China and working there was after a few meetings with high officials, I started hearing of the idea of an ecological civilisation. I thought, stop, what do you mean? I said, I admire the skill of the Communist Party in coming up with slogans, is this just a slogan? And that got a laugh, then they said, no, we really believe it. And they’ve divided the world into eight different divisions, along the lines that I’ve been talking about, and they’ve thrown hundreds of their best people at it. And they invited me to join the panel on rewriting the Chinese legal system, which I advised them on. And this, I take enormous encouragement from this because they really are taking this seriously – this a direction from the top – to reconceive things. The world doesn’t stop, things are still going on, but in the meantime redesign everything in a way that is practical and can be tried in the internal Chinese system, and maybe exported. And that’s so far beyond what’s going on in Australia, or France, or Germany, or the United States. It’s an intellectual creative beacon of very pragmatic hope for me. What I’m hoping is that instead of having to be the ruler of the world to do this, what we’re seeing is that one country is throwing hundreds of its best people at this, inviting hundreds of foreign experts to join, and developing something that then could potentially be open-sourced and greatly speed up the transition that we need to do.

Legislative change takes time, but time is exactly what we’re short on when it comes to the changes that are necessary to combat climate change, pollution, and the general environmental destruction that our species is currently inflicting on the Earth. The changes that are necessary need to be made on a global scale, and as big as China may be, we need changes everywhere. What sort of time frame are you working towards when it comes to implementing these changes you think are necessary, and do we have enough time?

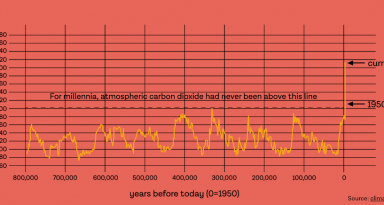

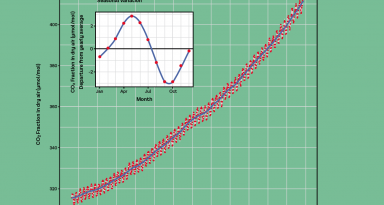

I’m working on a ten-year time frame, which I’ve frequently stated, based on some good science that we need to make some significant changes in the next ten years. Can we do it? Yes, I think we can do it because of several factors. One is that economics really is on the side of people and the planet now: renewable energy really is cheaper. When I was a young person I would stand up and say that we need renewable energy, and people would say, “well, you’re a nice, idealistic young person, but the economics won’t allow it.” Now it’s really different – the economics does allow for clean energy because it’s cheaper than dirty energy. But, back to the timescale – economics, the markets alone will not deliver fast enough because of this problem of the incumbents sitting in the river. Therefore the second thing you need is for citizens like us to rise up, use legal tools, and slay the incumbents so that the market can actually deliver. And third, I would say that something that also gives me hope, is that this is really all about consciousness. It struck me recently that environmental problems are mental problems – no more than that. They’re problems of how we think, how we behave; only that. If we can have a revolution of consciousness, about how we think about these things, then it becomes possible to transform very quickly.

Indeed, but despite all this we do face a major barrier: those who think that there’s no reason to change their behaviour, or who couldn’t be bothered to change because it’s inconvenient for them. What do you have to say to those who don’t think that there’s any reason to change our behaviour or that we face any pressing environmental concerns?

I say, wake up and listen to children and what they are telling us.

< Seasons in the sun | Our place in the world >