“O! that that earth, which kept the world in awe,

Should patch a wall to expel the winter’s flaw!”

Hamlet, Act 5, Scene 1, by William Shakespeare

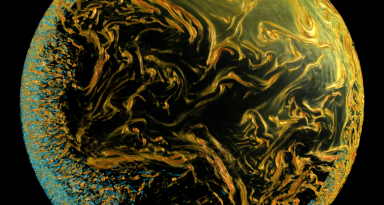

The Sun has always reigned as a god in my world. Heedless of health warnings, I long for the penetrative heat of its rays on my skin, the burnish and ripeness and Southern hemispheric tang it bestows on daily life, and the brilliant light – both literally and figuratively nourishing – that so many painters have been driven to chase, moving to Cornwall, to Arles, to Tahiti, the better to trap it on canvas. Perhaps my old soul was Aztec – or else devoted to Ra, the ancient Egyptian overlord of Heliopolis.

At the cheesy end of my solar obsession, I have seen Danny Boyle’s 2007 sci-fi thriller Sunshine many times over, never tiring of his fictional astronauts’ nail-biting mission to reignite a dying Sun – a mission that one crazed character in the movie, in the grip of a psychotic form of sunstroke, wishes to derail. Slave to the kamikaze urge to fly into the heart of the solar furnace, he has a body to prove it: skin crackled to a crisp; lidless eyes, peeled back; face and body, charred and flayed like an anatomical model. I think of his deformed madness sometimes when I wonder about my own irrational addiction to summer, the season (as I see it) of expansiveness and fulfilment, but tinged with a reckless allure. We are told not to look into the Sun because the looking will blind us, but the intrusive thought is always there, goading us to stare regardless, as if by proving ourselves equal to its too-bright glare we might somehow exalt ourselves.

Besides, nothing escapes the Sun’s magic touch. It is transformative. Rough urban landscapes glisten. Stone cities like Edinburgh, Antwerp or Rome acquire the sheen of a Jerusalem: in summer, they are golden. There is a bodily dimension to consider as well, as the Sun turns us into Vitamin D factories, enhancing our mood and gifting our skins a pleasing warmth – a visible glow. On a summer’s morning, as bright yellow fingers of light poke into our bedrooms around the curtain’s edge, how many of us will leap out of bed, jolted awake, electrically charged for the day ahead?

We are affected profoundly by the climate, and by climate changes large and small. The human body reacts swiftly to alterations in humidity, atmospheric pressure, cloud cover or wind, just as it reacts to light and dark. Blood pressure is higher in winter, when lower temperatures cause our blood vessels to narrow; and lower in summer when our vessels dilate, making us flush, and contributing to that feeling of relaxation and wellbeing the season induces. We are sensitive to shifts in barometric pressure, too. Which is why people can sense when a storm is coming: the depression is something they feel in the air-filled tubes of their sinuses, or in their joints, which can become painful. Low barometric pressures can also cause headaches and difficulty hearing. In 2011, Japanese researchers published findings in the Journal of Internal Medicine demonstrating a direct link between patients suffering migraines and a sensitivity to atmospheric pressure.

We are affected profoundly by the climate, and by climate changes large and small. The human body reacts swiftly to alterations in humidity, atmospheric pressure, cloud cover or wind, just as it reacts to light and dark. Blood pressure is higher in winter, when lower temperatures cause our blood vessels to narrow; and lower in summer when our vessels dilate, making us flush, and contributing to that feeling of relaxation and wellbeing the season induces. We are sensitive to shifts in barometric pressure, too. Which is why people can sense when a storm is coming: the depression is something they feel in the air-filled tubes of their sinuses, or in their joints, which can become painful. Low barometric pressures can also cause headaches and difficulty hearing. In 2011, Japanese researchers published findings in the Journal of Internal Medicine demonstrating a direct link between patients suffering migraines and a sensitivity to atmospheric pressure.

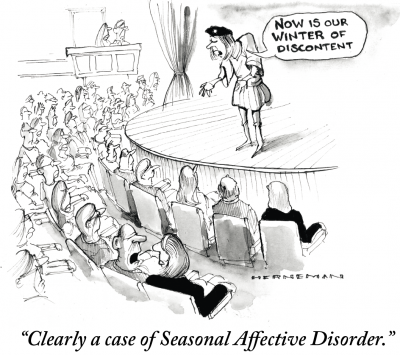

But it is the emotional response to climatic change that is more complex and troubling. With the diminishment of sunlight that attends the approach of winter, thousands of people in climates cold and warm (up to 9.9% of the population in Alaska, but as high as 1.4% in Miami [CHECK]) experience the depressive mood disorder known as SAD, or Seasonal Affective Disorder. With a raft of symptoms that include lethargy, weight gain, a tendency to over-sleep and listlessness, SAD engenders a kind of waking hibernation. In acute cases, sufferers report feeling worthless, hopeless, and sometimes, suicidal: they have trouble concentrating, trouble sleeping, and a flat-lining libido.

To the extent that SAD affects me personally, I am prey to feelings of intense anxiety at summer’s end, as I start to dread the onset of my seasonal depression. I know very well that there are treatments I might seek out: light lamps, melatonin supplements, CBT. But so far I’ve resisted them, perhaps because despite acknowledging that we have animal natures, primitive responses to the climate that are beyond our control (and equally evasive of conscious awareness), I still incline towards philosophical explanations.

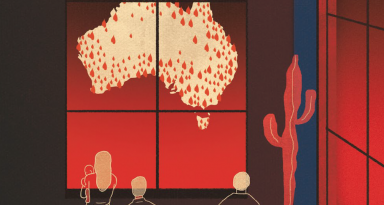

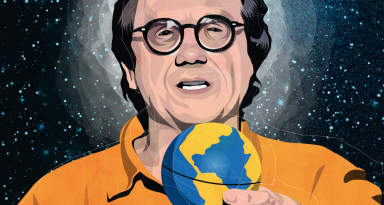

Recently I came across the term solastalgia. Coined by the Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, the neologism combines solace, desolation and algia, (from the Greek for pain) to give shape to the distress of seeing a familiar environment ruthlessly transfigured by drought, fire or flood. Solastalgia, in other words, names the stress and helpless anomie induced by environmental change.

In a paper published in Australasian Psychiatry in 2007, Albrecht clarified the coinage. As opposed to nostalgia – the melancholia or homesickness experienced by individual when separated from a loved home – solastalgia is the distress that is produced by environmental change impacting on people while they are directly connected to their home environment.’ It is a homesickness you feel without ever leaving home. SAD, it seems to me, qualifies as solastalgia on a small scale – its apt acronym denoting a lament for the loss of summer light once autumn’s shade arrives. But the environmental crisis we face now, as a planet, scales up our eco-anxieties to new levels.

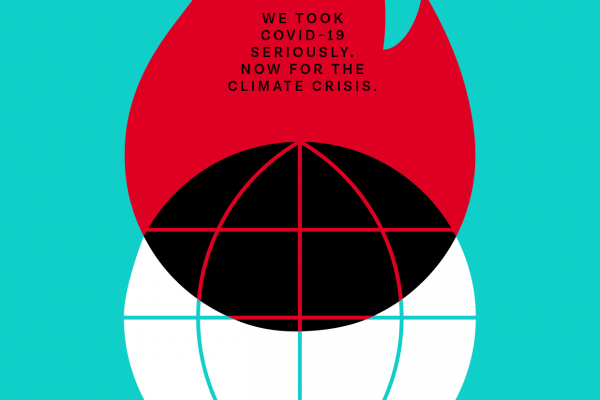

The mental toll of our environmental degradation is only now impinging on our collective consciousness. Papers have been published about suicides among farmers made destitute by crop-searing heat, and about the mental health problems among Americans who have fallen victim to uncontrollable fires and devastating storms. In 2017, the APA approved ‘eco-anxiety’ as a clinically valid diagnosis. All of it is a form of mourning, the grief we associate with SAD, writ global.

Among teenagers inspired by the urgent exhortations of Greta Thunberg, that grief and anger is virulent and palpable. The springtime of their young lives ought, by rights, to be a time of growth and soaring potential. But today’s youth are instead being forced to reckon with a contraction of their horizons and a planet-sized shrinking of temperateness and life-supporting quality that may never end. For the young, there’s a very real possibility that, for them, summer – the high season of their lives – might never arrive.

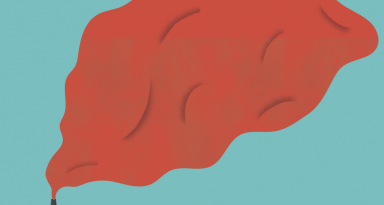

The irony is that all the while our Earth grows warmer, the Sun’s light, increasingly obscured by particulate pollution, grows ever dimmer. As the myths of old might have it, the Sun will be ferried away on the barge of a solar deity, never again to brighten our days.

< Our ultimate fragility | Client Earth >