“Man is everywhere a disturbing agent. Wherever he plants his foot, the harmonies of nature are turned to discords.”

– George Perkins Marsh

Our classes were often conducted in low light, a blurry, soft-spoken figure gesticulating from the front. “Don’t just flick on a light switch,” exhorted Frank Fisher. “Think about the process involved in generating the energy for that light – all the way from the coal-fired power plant to this light switch – and ask yourself, ‘Do you really need that extra bit of light?’” His suggestion to combat the involuntary switching on of lights when entering a room: place them at knee height (although when he said this, I could always picture a cracked switchboard and scuff marks circling the knee-height light switch).

Peripatetic classes, lectures in the bush, light-free tutorials: the aim of all these activities was to shift our perspective, to make us view the world from a different angle – to make our thinking “wild”, as he liked to say. This mild-mannered professor of environmental science wanted to make his students “wild thinkers”; a group of people who would help transform the way our society was structured.

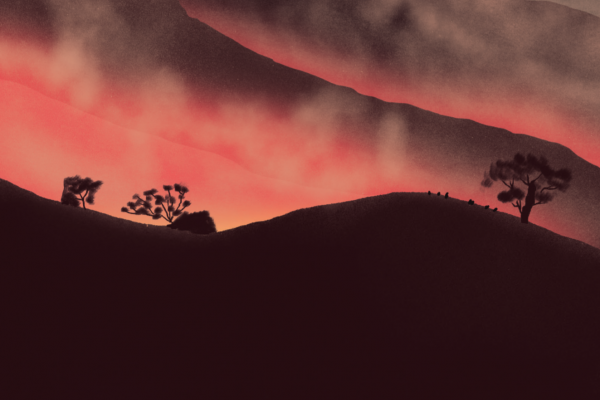

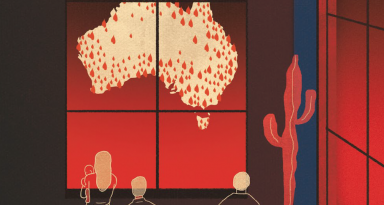

It’s most likely an understatement to say that Frank would be disappointed with the direction the world has taken in the twenty years since I sat in his classroom. 2019 was Australia’s hottest and driest year on record, with the annual national mean maximum temperature 2.09 °C above average and rainfall 40 per cent below average. Bushfires raged across the country, burning 186,000 square kilometres of land and killing one billion animals. In 2014 Australia’s Carbon Tax was repealed. In 2018, the current Prime Minister held aloft – in parliament, no less – a lump of coal like a trophy; and that was before he was elected. Elsewhere in the world, it’s little better. The world is losing an area of forest the size of the UK each year. The last six years are the six hottest years on record globally. According to the UN, there are “46,000 pieces of plastic” per square mile of ocean, a phenomenon which finds its apotheosis in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which boasts some 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic.

Frank would probably also be disappointed by my reference to what is wrong with the current state of the world. “Identifying what is wrong is easy,” he would say. “It’s not hard to identify that something is lacking, or even what that something is that it lacks. Pinpointing how to fix the problem is more difficult, and while important, without action it is ineffective.” It’s not that he didn’t value the ‘what’ and the ‘how’, it’s just that he thought we needed to put more emphasis on action; on doing. We know that the tap is leaking – we’re annoyed by the dripping and we’re upset by the waste. But rather than simply pointing and complaining, we must start trying to fix the tap.

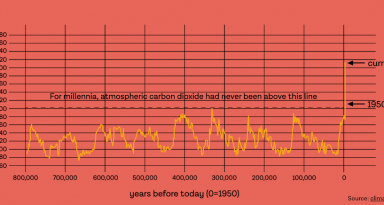

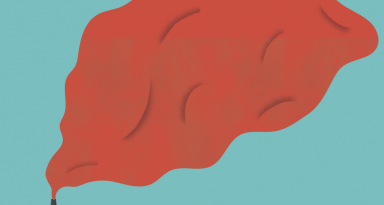

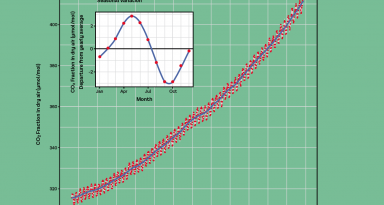

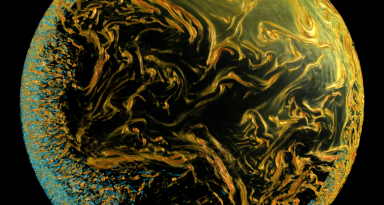

There’s a phenomenon that is referred to as environmental conditioning, which is, according to the OECD, “the modification of the environment of one or more organisms by their activities, including reaction and co-action (liberation of oxygen, for example, by water plants in an aquarium)”. By releasing massive amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, humans in the 20th century are certainly engaging in their own form of environmental conditioning. But it is another form of conditioning that I think is at the heart of our current malaise, one in which we are passive rather than active participants. While we may be conditioning the environment, we are also becoming conditioned to the current environment – adapting to the state of affairs that sees rising temperatures and polluted rivers, failing crops and cleared rainforests. We are becoming conditioned to the devastation and destruction around us; unmoved the effects of climate change; insensitive to the legacy we leave for future generations. By becoming accustomed to this new environment, we do nothing. Genetically, humans have adapted to cope with various environmental conditions. Excess layers of fat to deal with the cold, sweating to deal with the heat. Are we adapting psychologically to deal with climate change by becoming numb to its effects? Is it inconvenient to look at the causes front on, to implement the solutions that we know to be necessary?

When I say ‘we’, I refer mostly to those over 50; those who may not be around to feel the full force of Nature’s response to our tinkering with the Earth’s systems. Younger generations seem to have a more visceral response to the inaction that permeates all levels of society, from individuals to governments to corporations. And that is who Frank Fisher was talking to in our classes: he was trying to exhort a group of 20-somethings to unearth and embrace the wild thinker within, as he was certain that it was only wild thinking that could save us.

Twenty years after those darkened classes, Frank is no longer with us, ultimately dying from a brain tumour in 2012. His spirit remains in the ideas and energy he passed on to his students, including me: I still take pause before flicking a light switch, thinking of him when I feel my way through a dark room in the evening for a glass of water. And when I see gridlock in city traffic, I am reminded how he campaigned – unsuccessfully – for Melbourne to have free public transport. An idea that seems obvious, yet somehow unachievable all at once.

I’m not doing Frank any justice by mentioning light switches and buses; his ideas ran much deeper than this. What he really taught me, and countless other students I imagine, was how to look within myself and unearth my wildest thoughts, and, importantly, to turn them into action. “Just that you do the right thing,” Marcus Aurelius writes in Meditations. “The rest doesn’t matter. Cold or warm. Tired or well rested. Despised or honoured. Dying... or busy with other assignments.” Just as Aurelius advised, Frank showed through his five-decade battle with Crohn’s disease and his relentless fight against environmental destruction that we must not find excuses for inaction. Instead, we must do all that is in our power to effect positive change in the world – no matter how cold or tired or busy we might be.

< Ethical dilemmas | 6 thinkers >